This Alien Life: Privatized Prisons for Immigrants

The small town of Florence, Arizona, sits at an epicenter of a new boom in private prisons for immigrants. The one-lane highway from Tucson to this desert prison town runs through cacti, red rock, and occasional mountains. Then out of nowhere, a roadside sign breaks the spell: "State Prison: Do Not Pick Up Hitchhikers."

Florence hosts Arizona's state prison, two privately run prison complexes, and one Department of Homeland Security (DHS) immigration jail.

Florence "has a prison economy and a prison consciousness," says Victoria López, an attorney who runs the town's only pro bono legal center that helps immigrant detainees fight their cases. "Florence is another world. Here most locals are people whose families have for generations worked in the prison system. Life revolves around the prisons."

Border Watch: Our Ongoing Coverage Fencing the Border: Boeing's High-Tech Plan Falters The Life and Death of a Border Town |

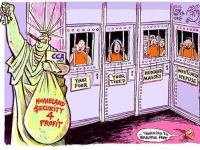

As the government invokes national security to sweep up and jail an unprecedented number of immigrants, the private-prison industry is booming. In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks on New York, immigrants have become the fastest growing segment of the prison population in the U.S. today. In fiscal year 2005, more than 350,000 immigrants went through the courts. "A growing share of them committed no crimes while in the United States - 53 percent this year, up from 37 percent in 2001 - even though Bush administration officials repeatedly have said their priority is deporting criminals," the Denver Post reported.

From Mining to Prisons

Many locals have family roots in the mining industry that was the lifeblood of rough and tumble town until the silver boom petered out. Around the turn of the 20th century, the territorial prison moved to town. But the town really came back to life after Tennessee-based Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) one of the nation's biggest prison companies, built two prisons in Florence, and the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) began renting bed space, and then built its own prison out of a town's old World War II prisoner-of-war camp. The influx of immigrant prisoners created jobs that drove the economy and sparked construction of new housing complexes on the outskirts of town, followed by big retailers such as Wal-Mart.

In 2000, the industry was carrying more than $1 billion in debt and was violating its existing credit agreements. CCA saw its stock plummet 93 percent and Business Week noted that the correction "industry's heyday may already be history."

At the time, the American Prospect, a national magazine, explained the decline:

Immigration Prisons by the Numbers " Some 1.6 million undocumented immigrants are being held in some stage of immigration proceedings. "ICE holds more inmates a night than Clarion hotels have guests, operates nearly as many vehicles as Greyhound has buses and flies more people each day than do many small U.S. airlines." |

"The private-prison industry is in trouble. For close to a decade, its business boomed and its stock prices soared because state legislators across the country thought they could look both tough on crime and fiscally conservative if they contracted with private companies to handle the growing multitudes being sent to prison under the new, more severe sentencing laws. But then reality set in: accumulating press reports about gross deficiencies and abuses at private prisons; lawsuits; million-dollar fines. By last year, not a single state was soliciting new private-prison contracts. Many existing contracts were rolled back or even rescinded. The companies' stock prices went through the floor."

Then came the the September 11th attacks on New York in 2001. The government began to target non-citizens with mass arrests during sweeps through immigrant communities, increased prosecutions of undocumented border crossers, and the use of immigration law to hold people while looking for criminal or terrorist charges against them. The INS was subsumed into a new agency named the Department of Homeland Security.

The government claims that locking up people without legal status is the only way to ensure that they do not disappear into the country. A December 2004 DHS report from the Office of the Inspector General concluded that all the evidence proved the "importance of detention in relation to the eventual removal of an alien. Hence effective management of detention bed space can substantially contribute to immigration enforcement efforts."

The speed and scope of the Bush administration round up and jailing of non-citizens created a dramatically increased need for immigrant detention space. And saved the flailing corrections industry.

The DHS-run Special Processing Center is a massive one-stop-shop, where immigrants can be jailed, tried in an immigration court, appealed before an immigration judge, and ordered deported-all without leaving the self-contained complex. While DHS does not refer to its facilities as jails, the Special Processing Center in Florence is ringed by concertina wire, surrounded by chain-link fences, with inmates locked into cells. They face zealous prosecution and in many cases are left to languish for weeks and months without trial or sentencing.

The complex in Florence is part of a 300-facility-strong network of immigrant incarceration facilities. The average time an immigrant is detained is 42.5 days from arrest to deportation. At $85 a day per detainee, that adds up to $3,612.50 per person. In 2003, DHS was holding 231,500 detainees, and the budget to cover this was $1.3 billion. Since 2001, the DHS budget for detention bed space has increased each fiscal year as has the number of beds. In 2003 there was more than $50 million slated for the construction of immigrant jails.

Corrections Corporation of America

Contracts for these new jails flowed to the private prison industry despite the previous history of mismanagement and scandal. Yet the problems have not been solved - today detainee advocates still decry the treatment of immigrant inmates. They accuse prison companies of cutting corners in training guards and in providing basic services. The government has done little to regulate prison administration, but has sanctioned exploitive labor practices and rip-off telephone costs for inmates.

Philippe Louis-Jean, a veteran who saw combat in Iraq detailed some of abuse. A Haitian immigrant who had lived in the U.S. since he was five, the Marine had advanced quickly though the ranks. On return from Iraq, when he attempted to have his battlefield promotions honored, his superiors looked into his past and found an old military conviction for which he was served 37 days. The government used that record to begin deportation proceedings and threw Louis-Jean into CCA-run San Diego Correctional Facility (SDCF). He was appalled by conditions and treatment.

"The guards would scream and shout at us as if we were little kids. If we would ask them to stop, they would threaten to lock us down for a few days, which would happen constantly. Three people being locked in a two-man cell, in a 12 x 7 room. This happened a lot; sometimes as punishment for the actions of one or two inmates, the other 105-115 detainees would suffer."

"Other times, it seemed 'just because.' A lot of the detainees would be missing money on their accounts, which I was recently told by a detainee who keeps in contact with me was being stolen by the staff, according to [an] OIG investigation. We would get underserved during meal times. When we complained to the unit manager she would say that we were given the right amounts, which in my opinion is the appropriate portion for a ten or eleven year old. Some of the guards and staff would curse at us. They would purposely lower the televisions so we couldn't hear them, just to mess with us. During our free time they would take their time turning on the phones so we wouldn't be able to call our families. Just to be cruel."

One of his guards, an ex-marine, told Louis Jean "he was taught to not really pay attention to our complaining and to treat us like second-class citizens ... since we will be deported anyway.

A 2003 report by the DHS Inspector General forcefully condemned the treatment of immigrants inside various jails in it report, "The September 11 Detainees: A Review of the Treatment of Aliens Held on Immigration Charges in Connection with the Investigation of the September 11 Attacks." Infractions included routine abuse of basic prisoner rights, mental and physical abuse, denial of health care and medical treatment, prison overcrowding, and a lack of working showers, and toilets.

Despite a long record of problems, CCA continues to promote privatization and win contracts. "The private prison industry, to increase the demand for its services, exerts whatever pressure it can to encourage state legislators to privatize state prisons," wrote Sharon Dolovich in the Duke University Law Journal. "[T]he industry is adept at lobbying legislators and targeting campaign contributions to promote its privatization agenda."

Indeed, some critics charge that the company's success is related to its deep rooted ties to elected officials. In addition to CCA's record of campaign contributions to the Republican Party since 1997, there are significant connections between executives and government officials. J. Michael Quinlan, former head of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, has been an executive at CCA for the past decade. CCA's chief lobbyist in the state of Tennessee is married to the speaker of the house. And CCA is a member of the American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative group that writes and pushes bills on policy such as sentencing guidelines.

For the second quarter of 2005, CCA announced that its revenue had increased three percent over last year, for a total of almost $300 million. CCA calculates that it expenditure of $28.89 per inmate, per day allows it to make a daily profit of $50.26 per inmate. Meanwhile, on July 1, 2005, the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement awarded CCA contracts to continue running the 300-bed Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey and the 1,216-bed San Diego Correctional Facility. Both of these contracts are for three years with five three-year renewal options. In 2005 CCA also secured new prison contracts with the Kentucky Department of Corrections, the state of Kansas, and the Florida Department of Management Services.

Business is good for CCA and the more people it stuffs into its prisons the better it becomes. "As you know, the first 100 inmates into a facility, we lose money, and the last 100 inmates into a facility we make a lot of money " CCA Chief Financial Officer Irving Lingo said on a 2006 company conference call.

Wackenhut

Florida-based Wackenhut, a major private security company, has also received a great boost in the years since the September 11th attacks on New York. Its poor record has not undermined its ability to reap lucrative government contracts. Before 2001, Wackenhut, like CCA, had been at the center of all manner of inmate-abuse scandals: Guards were caught having sex with underage inmates, there were routine reports of extreme mistreatment of inmates, and there was even a disproportionately high level of deaths in their facilities.

Wackenhut CEO George Zoley has been flippant about the cases of abuse. After a CBS Television report exposed the repeated rape of a 14-year-old girl at a Wackenhut juvenile jail and two guards were found guilty, Zoley said, "It's a tough business. The people in prison are not Sunday-school children." Still more worrying was Wackenhut's record with inmate-on-inmate killings, which, contrary to public perception, are not very common in America's prisons. In 1998-99 alone, Wackenhut's New Mexico facilities had a death rate of one murder for every 400 prisoners. For the same period in all U.S. prisons, the rate was about one in 22,000.

Wackenhut's most visible response was to change its name. Now as the GEO Group, it is still headed by George Zoley, and it continues to run the Wackenhut facilities and get new contracts. In 2005 the State of California Department of Corrections gave GEO the contract for the housing of minimum security adult male inmates at the 224-bed McFarland Community Correctional Facility estimated to generate $4.1 million in annual revenues. On August 8, 2002, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) awarded GEO a contract for the company's Broward Transitional Center in Miami. The contract has been extended through September 2008.

Under a 2005 ICE contract GEO also manages the Queens Private Correctional Facility, where it expects to reap $10.5 million in annual revenues. The Mississippi Department of Corrections also renewed GEO's contract for the continued management and operation of the 1,000-bed Marshall County Correctional Facility. Meanwhile, also in 2005, GEO announced a merger with Correctional Services Corporation (CSC) that will add approximately $100 million in revenue to GEO's coffers. GEO is especially excited about the earning potential from CSC's 1,000-bed expansion of its State Prison in Florence, Arizona.

GEO executives are overjoyed about the boom in business. In 1999, the feds farmed out less than 3 percent of beds; but seven years later, the number had reached almost one in five. "That's a remarkable turnaround," GEO Group CEO George Zoley told his fellow executives."And it's continuing to lead in that direction, that for minimum-security beds by the BOP (Bureau of Prisons) to house criminal aliens and illegal aliens by either the U.S. Marshal Service or the BOP or immigration service, they are turning to private companies."

"I think we're in a new era that I could never predicted, really, this scale of acceptance by the federal government. We talked about it for many, many years, but we're finally on the verge of it... ." added Zoley.

Cost Savings

The corrections industry has routinely argued that privatizing prisons dramatically lowers costs. A 1996 U.S. General Accounting Office report concluded, however, that there was no clear evidence supporting this contention.

Prison companies do have clear advantages over other corporations: They are able to save large amounts of money on labor practices that would illegal under any other circumstances. Inmate jobs in all prisons pay a pittance, but immigrant prisons are even worse. Because DHS guidelines mandate that non-citizen prisoners cannot earn more than $1 per day, the company gets janitors, maintenance workers, cleaners, launderers, kitchen staff, sewers and grounds keepers at almost no cost.

With the increase in prison beds for immigrants comes the pressure to fill them-- a scenario that has immigrant advocates extremely worried. Isabel GarcÃa, attorney and human rights activist in Tucson, sees the drive to jail immigrants as fueling the same prison-industrial complex that first flourished with the war on drugs.

"The war on drugs has conveniently become a war on immigrants," says GarcÃa, "and there is a lot of money to be made in detaining immigrants." The grown industry of incarcerating immigrants is facilitated by the tight connections between the private-prison industry and the federal government and the extent of the industry's powerful and well-funded lobby. GarcÃa worries that the profit motive behind detaining immigrants will promote the criminalization of immigrants.

In the name of national security, the Department of Homeland Security has let industry lead the way in implementing systems and procedures that purport to protect America from future terrorist attack. However, in many cases it is immigrants and non-citizens with no connections to terrorism who get tangled in the net.

Adapted from Targeted, by Deepa Fernandes (Seven Stories Press, 2007) Additional research by Terry Allen.

This article was made possible by a generous grant from the Hurd Foundation.

- 23 Private Security

- 24 Intelligence

- 116 Human Rights

- 176 War Profiteers Site