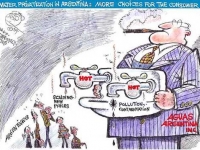

Argentina Water Privatization Scheme Runs Dry

Rio de la Plata ("the Silver River") separates Buenos Aires, the

capital of Argentina, from Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay. For 500

years, it has also been called "la Mar Dulce" as visitors, confused

by its beauty and size, mistook it for a freshwater sea. Today,

though, the river has another distinction: it is one of the few

rivers of the world whose pollution can be seen from space.

"Living by the river is a curse," says Alejandra, a mother of three

with sad eyes. "I am a single mother, with no work, and I don't know

what to do with my children." Alejandra lives in a very poor

neighborhood known as "Villa Inflamable."

The district has been given this name for a chilling reason:

surrounded by chemical and petroleum industries, the zone's

combustibility is considered a time bomb. Villa Inflamable is in the

heart of the South Dock Petrochemical area, where, as of 1997, some

3000 companies continuously dump their sewage into Riachuelo, "the

little river".

Adding to this intense pollution is the sewage waste of five million

customers of the privatized water company Aguas Argentinas, which is

dumped directly into the river each day without treatment. Three

kilometers upstream Aguas Argentinas treats the very same water for

use by the same population.

A World Bank case study

Aguas Argentinas is a case study of the rush to privatize water

services in the last decade by European and U.S.-based companies,

backed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

The deal made between Argentina's water authority and a consortium

that includes the Suez group from France, the largest private water

company in the world, and Spain's Aguas de Barcelona, in May 1993,

established a new private entity, named Aguas Argentinas, with the

help of the World Bank which also bought a small stake in the

consortium. According to a study by Dr. Malpartida's

Ecology and Environment Foundation, the new company was "the biggest

transfer of a water service and watershed into private control in the

world" encompassing a region with over 10 million inhabitants.

Privatization Plans Plummet Today 460 million people around the world are dependent on private However now the world's primary water corporations have decided David Hall of Public Services International Research Unit describes Suez' In February of 2003 the water and sewage concession in the capital of |

As a result, according to Daniel Azpiazu, a researcher at the Latin

American Faculty for Social Sciences, residential water rates

increased 88.2% between May 1993 and January 2002 although there was

"no relationship between this rate and the consumer price index

(inflation rate), which was 7.3% for the same period."

Azpiazu says this provided the company with net profits of 20%, which

he says is far higher than is "acceptable or normal" for the water

industry in other countries: "In the United States, for example,

water companies earned between 6-12.5% profits in 1991. In the United

Kingdom a reasonable rate of profit for the sector is between 6-7%.

In France, 6% is considered a very reasonable return on investment."

Yet this rate increase did not translate into higher quality or

quantity of service. In 1997, the company was found to have failed to

honor 45% of its contract commitments for improvement and expansion

of services, resulting in massive pollution.

Unfit for human consumption

Aguas Argentinas transports sewage waste of 5,744,000 people, but

according to a December 2003 study by the Argentine Auditor-General (AG)

only 12% of the total receives full sewage treatment. The rest,

according to the auditor, is dumped tin the Rio de la Plata in the

Berazetegui zone.

Individuals and municipal authorities in Berazategui, together with

the nearby municipalities of Quilmes and Berisso, recently sued Aguas

Argentinas for the contamination of the river, asking for $300

million in compensation.

"From the beginning of the year", said Fernando Gerones, mayor of

Quilmes, "we have been trying to bring attention to the problem that

the drinking water for the region, which is drawn in Bernal by Aguas

Argentinas, has its source just 2.8 kilometers from the coast where

sewage is dumped in Berazetegui."

Aguas Argentinas is terse in denying that the pollution present in

the water at its source is passed on to consumers. "The possible

increase in contamination of the water of Rio de la Plata does not

affect the quality of the water produced and distributed by the

company," a company spokesperson said.

However, a study published in El Porteo magazine showed that the water in

"seven districts of Greater Buenos Aires is unfit for human

consumption, containing nitrate levels that are three times too

high." The findings were corroborated by a study conducted by the

Environmental Chemistry and Biogeochemical Laboratory at the Faculty

of Natural Sciences in La Plata, which went even further, revealing

that some of the fish of the zone were contaminated with PCBs. This

highly carcinogenic, and consequently banned substance, is a

component in various chemical weapons, including napalm and the

defoliant "Agent Orange".

One month ago, when the courts commanded Aguas Argentinas to fulfill

its contract and construct a water purification plant in Berazategui

within 18 months, company spokespeople first replied that

"technically, this is not a responsibility of the company, but of the

government." In a later communique, after this argument was refuted,

the company changed its mind: "we are complying with the judge's

wishes, but environmental improvements require more than a treatment

plant: they require a much wider plan."

Pocketing rate hikes

The company has long promised to finance major improvements and even

hiked rates twice to pay for the expected costs. But in 2003, ETOSS,

the regulatory body that oversees Aguas Argentinas, slapped the

company with a 55 million peso fine when they discovered that the

company had never implemented their construction plans.

Indeed Aguas Argentinas has invested mostly in small improvement

schemes rather than major investments in additional production

capacity that a government operator might have undertaken.

The World Bank's Operations Evaluation Department praised this

approach in a 2003 report, which says: "Under the same contract, the

concession managed to postpone indefinitely costly additions to the

capacity of the sewage interceptors simply by accelerating

maintenance of the existing interceptors."

However, Aguas Argentinas' frugality in matters of infrastructure has

created a vacuum where the core service of providing water for

drinking and sanitation should be. Liliana de la Serna, proprietor of

a popular dining room for children in Quilmes, a province of Buenos

Aires, describes the daily reality. "There's almost no water here.

Several blocks in the district aren't connected to the network, and

were contaminated after a break in the sewage lines."

Aguas Argentinas promised to provide bottled water, but ignored their commitment after one delivery. In the meantime, the rest of the district receives "intolerable,contaminated water, and not much of it at that."

When contacted about the rate hikes, Aguas Argentinas refused to

comment on the propriety of continual rate hikes.

Cancel the contract?

Four months ago, when the government of Nestor Kirchner cancelled the

privatization of the Argentine Postal company, Aguas Argentinas, was

believed to be next on the list. In the influential newspaper Clarin,

the the Minister of Economic Planification Julio del Vido said it

would take a hard line in its negotiation with Aguas Argentinas,

demanding substantial new investment, maintenance, improvement

of the network, as well as the quality of service. "And if they don't

sign, the contract will be cancelled."

There was even talk of prosecution. Leandro Despouy, president of the AG,

also pointed to the existence of cases of "non-fulfillment of contracts that

must be investigated by the Department of Justice, to determine whether there

is criminal or administrative culpability on the part of the company."

Aguas Argentinas soon found themselves with another surprise: at the

end of 2003 the government informed them that they faced new

penalties of 8.6 million pesos for non-fulfilment of contract. Weeks

before, the company had been charged with a penalty of 3 million

pesos, partly as punishment for a short, unpredictable cut in the

service that affected 6 million people in September 2003.

On February 13, following a meeting between the Argentinian goverment

and Suez' board of directors, the company issued a press release

announcing the achievement of "the basis of a negotiation to set down

in a lasting way an economically balanced agreement for all parties,

thus

confirming its will to continue with the Aguas Argentinas mission."

It remains to be seen whether the government will back down from the

confrontation, force the company to clean up its act, cancel the

contract or if the company will pull out altogether, as it has in

several other countries. (see box)

Sebastian Hacher is an independent journalist and photographer currently based in Argentina. Justin Podur is a writer and translator on Latin American issues.