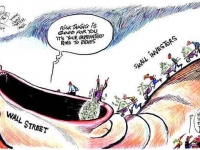

Banking on Elections

Finance sector invests heavily in candidates

When Phil Gramm came out of the Tavern

on the Green one recent August morning, his disposition turned edgy.

The former Texas Senator the long-time banking committee chair is now a

vice chairman of the Swiss financial corporation UBS. He'd just passed

some pleasant hours hobnobbing with comrades in the money trade, all

lured to New York by the chance to make profitable connections during

the Republican Convention. But Gramm wasn't keen on talking to waiting

journalists, certainly not to the CorpWatch team.

Robert Rubin seemed quite at ease sitting next to Teresa Heinz Kerry at

the Fleet Center in Boston, home to the Democratic Convention in July.

The Clinton Treasury Secretary, former senior partner at the investment

company Goldman Sachs, is now chairman of the executive committee of

Citigroup. There was no chance of journalists bearding him in the

candidate's box - at least none who would ask uncomfortable questions.

There's an old labor song that says:

"The banks are made of marble,

with a guard at every door,

and the vaults are stuffed with silver

that the workers sweated for."

Today, the banks attempt to disarm their critics with patron-friendly

public relations like Citibank's gushy "live richly" campaign, which

advises everyone that money doesn't really matter. What counts are

"hugs." Did you know that "the best table in the city is the one with

your family around it" and "some of the most exciting growth charts are

on the pantry door?" Moral: the best things in life are (almost) free.

So how come Citigroup CEO Sanford Weill, now the company's chairman,

collected $44.6 million compensation in 2003? Robert Rubin pocketed $17

million. These obscenely rich gentlemen must not be reading their

company's ads. (Or maybe the ads are only for the masses.)

Such feel-good promotion masks an industry that is anything but

benevolent. And to kill needed regulation for the public good, the

banks and financial services companies (that now includes insurance

companies, investment firms and stock brokerages) offer big money to

the candidates.

The Cash

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, a Washington-based group

that analyzes raw Federal Elections Commission (FEC) data, if one

combines all finance sector donors (including real estate, accounting

corporations, insurance and stock brokers) the combined total

contributions to Democratic and Republican parties and federal

candidates so far in this election season is a staggering $218 million!

Both major party presidential candidates are generously funded by the finance sector.

Over the course of his entire electoral career, six out of ten of

President Bush's top lifetime contributors come from the financial

sector. In the current presidential campaign, all ten of Bush's top

contributors come from the financial sector (accounting, banking,

insurance, stock brokers and investment companies).

According to summaries provided by the non-partisan public interest

group the Center for Public Integrity, contributions to Bush's

campaigns for Congress, Texas governor and the presidency through the

third quarter of this year show $353,000 from UBS Financial Services,

$445,000 from Credit Suisse First Boston, $505,500 from Merrill Lynch,

$493,000 from MBNA Corporation, and $343,000 from Goldman Sachs.

On

the Kerry side, contributions to the committees of Citizen Soldier

Fund, Kerry's Senate campaigns from 1984-2002, and Kerry's 2004

presidential campaign through June 30, 2004 included: Citigroup

$226,910, FleetBoston Financial Corp., $202,087, and Goldman Sachs

Group $190,750. And not far down in Kerry's list one can find JP Morgan

Chase and Bank of America, which recently merged with Fleet Financial,

Kerry's biggest backer during his congressional career.

common. (See Center for Public Integrity chart below.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Federal Election Commission data shows that Citigroup's Political Action Committee (PAC) has given the Republican party and its federal candidates $196,234 and given $92,693 to Democrats. Center for Responsive Politics reports list Citigroup individual and PAC donations to all federal candidates combined at over a million dollars.

UBS Americas PAC has given the Republicans $181,000 and the Democrats $129,100. All told UBS employees and PACs have so far given over $1.5 million.

The McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, passed in 2002, banned corporations and unions from giving soft money contributions directly to the political parties. Now only about 10 or 15 percent of contributions to the candidates comes from PACS. Most money comes from individuals who "bundle" their donations of up to $2,000 per candidate to make it clear who and what they represent. Although the campaigns say they voluntarily report who their bundlers are, they are not required to report it to the FEC.

In the Bush campaign, for example, the ten biggest financial services companies have bundlers who collect $50,000, $100,000, $200,000 or more. Often individuals make donations at the suggestion of a bundler in their company.

Alex Knott, political editor of the Center for Public Integrity, says, "Kerry has done the same thing. He has co-opted Bush's fundraising strategy -- though he doesn't have ten financial institutions [contributing]."

However, finance has jumped ahead of telecommunications to become Kerry's largest corporate benefactor, contributing at least $8 million through bundlers. Goldman Sachs executives account for four of Kerry's top-ranked bundlers. Also among them is Chad Gifford, former CEO of Fleet Boston and now the Bank of America chairman.

What do banks and their brethren want for the cash?

According to an August 2003 Public Citizen report entitled Bullish on Bush, E. Stanley O'Neal, CEO and chairman of Merrill Lynch, James Cayne, CEO of Bear and Stearns, and Thomas A. Renyi, CEO of the Bank of New York, saved a total of $1.9 million on their personal income taxes thanks to Bush tax cuts.

But far more important than saving on their executive's personal income taxes, these companies count on financial contributions to encourage politicians to cut dividend taxes and corporate income taxes, to wave through massive mergers, and water down regulations on accounting standards, money laundering, conflict of interest restrictions and other public interest requirements.

For example, in 1999, Kerry used his position on the powerful Senate Finance Subcommittee to support the merger of Fleet and BankBoston, even though the merger was opposed by local Democratic leaders and resulted in the layoff of 2,500 workers.

George Bush's favors to finance capital are so numerous it's difficult to list all of them, but the dividend tax cut, cuts on capital gains taxes and support for the privatization of Social Security are certainly at the top of the list.

The Math

The complex mathematics of contributions, access, lobbying, legislation and re-election rules both parties.

For example, the CorpWatch team asked Senator Gramm what role he had played in supporting the banking industry position against applying anti-money laundering sections to fraud against foreign governments. (See the interchange on video. )

As he exited the Tavern on the Green breakfast (passing a dollar-green topiary elephant placed there by Tavern staff to honor the Republican convention) Gramm blustered and feigned ignorance.

In fact, Gramm had filed amendments to anti-money laundering legislation that became part of the Patriot Act that allowed money obtained fraudulently to enter U.S. banks without triggering the anti-money laundering restrictions. Not only had he sponsored the amendments, but he had been lauded by the very sponsor of the Tavern on the Green breakfast, the Financial Services Roundtable.

The lobbying group, representing UBS, Citigroup and other financial giants, wrote a letter October 3, 2001, declaring that, "the Roundtable strongly supports all of Senator Gramm's amendments (#1-5), including Amendment #3, which deletes the provision making 'fraud against a foreign government' a predicate offense to money laundering. This overly broad provision would prevent U.S. banks from accepting deposits from foreign citizens in countries ruled by repressive regimes that prohibit their people from moving assets abroad. We should not prevent foreign citizens from seeking a safe haven in America for their assets." [Italics added.]

A committee staffer explains, "Gramm's amendment to strike 'fraud against a foreign government' was successful, and that language was removed. The general fear at the time is that it would have made tax evasion a predicate offense for money laundering." So, Gramm and his colleagues assured that U.S. banks would not be penalized for hiding the money of international fraudsters and tax cheats.

Finance de-regulation

But the big plum of finance de-regulation occurred in the waning years of the Clinton Administration, under no other than Treasury Secretary Rubin, now at Citigroup.

In this era of giant global companies eating up small ones, the big banks wanted, and they got, the abolition of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 which banned mergers of banks and other financial services companies (insurance, brokerage, investment companies) on grounds the mega-conglomerates would create conflicts of interest. While banking regulators and the courts had gradually been eroding the separations that existed in the law, it still remained the last government firewall against global financial oligopoly.

Citigroup was the leading company in the financial services industry that benefited from the law enacting the abolition. It was called after its chief sponsors the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act. Yes, the bankers' friend, Phil Gramm.

Citigroup lobbied aggressively and had a significant influence in shaping it, according to a source close to the drafting process. It needed the law to legalize its merger with the giant, Traveler's Insurance, which was allowed "temporarily" by President Clinton and Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, supposedly to allow time for the merged group to come into compliance.

Barbara Roper director of investor protection for the Consumer Federation of America (CFA), says, "The idea was that if Congress couldn't get legislation passed, the merger would unwind. It was never going to happen. Congress had a hammer over its head to get it to pass a bill. That added urgency to the process. Obviously, [Citigroup CEO] Sandy Weill and Citigroup were very influential in that process."

The CFA was strongly opposed to the bill. Roper says, "Our concern was there were safety and soundness risks when you combined banking with these other activities and that a bank whose securities or insurance affiliates got into trouble would face a strong temptation to bail them out. Then the federal deposit insurance system is at risk."

She says, "The other concern was that you'd have conflicts of interest where the banks would make loans to favored clients of their other businesses rather than loans based on credit worthiness of the borrower -- clearly an issue with Enron."

Consumer groups also argued at the time that increased concentration would create institutions of a size and complexity that would be impossible to regulate effectively.

In the end, despite initial resistance from Democratic Senators, all but eight Senators voted for the bill. By then, Treasury Secretary Rubin, who has acknowledged lobbying for the bill, had left the Clinton Administration. A month after it became law, he went to work for Citigroup.

How did citigroup and its lobbyists get the Senate to rush through the legislation? Roper says it's the usual Capital Hill story, "When the people who want the legislation passed make massive campaign contributions and the people who oppose the legislation are nonprofits who don't make campaign contributions, the deck is stacked in favor of passage."

Citigroup took the lead in proving the critics right. Decisions about lending and investment banking were tied to recommending client company stocks to investors. Regardless of the worth of the stock, Wall Street brokers would hype stocks in order to get companies to give them investment banking business. Financial regulators, as critics had warned, proved utterly unable to prevent these problems.

Caught in the crooked act, Citigroup was one of ten major Wall Street firms that agreed to pay a record $1.4 billion in 2002 to settle charges that they inaccurately and unfairly promoted stocks of companies that gave their firms lucrative underwriting contracts.

Among the President's top supporters are eight of those firms: Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, UBS Americas (previously known as UBS Warburg LLC), Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse First Boston Corp. (CSFB), Lehman Brothers and Bears Stearns. All were accused of knowingly dispensing false stock market advice; in settling the case they admitted no wrongdoing. But prominent personnel at some of the firms, including Merrill and CSFB, have also been criminally prosecuted.

Kerry's top ten presidential campaign donors include 3 of the same donors, UBS AG Inc.. Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley Dean Witter & Co.

Kerry's number two largest donor as of September 7, 2004: Citigroup.

Despite the big financial backing from finance, not all banking reformers have given up hope on Kerry. When the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America (NACA), ran a campaign against Fleet bank for engaging in predatory lending against low-income home owners, Kerry voted for a bill to regulate predatory lending.

NACA president Bruce Marks says that there was a concern at one point that Kerry was defending Fleet. Marks says, "We met with him, and he was fine. We never saw him being out there aggressively supporting Fleet." He says, "Kerry has been on the right side with the consumer on the banking issues [such as] predatory lending and disclosure."

Could the Kerry administration turn in a better record on oversight to the finance industry than the scandal plagued years of the Bush administration or the give-away era of the Clinton Administration? Perhaps, but maybe we'd better find out just what Citigroup's Rubin is whispering in Kerry's ear.

Lucy Komisar, a New York journalist, is writing a book on the offshore bank and corporate secrecy system.