CHINA: Ravaged Rivers

Last summer, Chinese government investigators crawled through a hole in the concrete wall that surrounds the Fuan Textiles mill in southern China and launched a surprise inspection of the plant. What they found caused alarm at dozens of American retailers, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Lands' End Inc. and Nike Inc., that use the company's fabric in their clothes.

Villagers had complained that the factory, majority owned by Hong Kong-based Fountain Set Holdings Ltd., had turned their river water dark red. Authorities discovered a pipe buried underneath the factory floor that was dumping roughly 22,000 tons of water contaminated from its dyeing operations each day into a nearby river, according to local environmental-protection officials.

In the more than two decades since international companies began turning to Chinese factories to churn out the cheap T-shirts, jeans and sneakers that people around the world wear daily, China's air, land and water have paid a heavy price. China has faced harsh criticism in recent months over the safety of exports ranging from tainted toothpaste to toxic toys. But environmental activists and the Chinese government are increasingly pointing to the flip side: the role multinational companies play in China's growing pollution by demanding ever-lower prices for Chinese products.

Prices on fabric and clothing imported to the U.S. have fallen 25% since 1995, partly due to the downward pricing pressure brought by discount retail chains. One way China's factories have historically kept costs down is by dumping waste water directly into rivers. Treating contaminated water costs upwards of about 13 cents a metric ton, so large factories can save hundreds of thousands of dollars a year by sending waste water directly to rivers in violation of China's water-pollution laws.

"Prices in the U.S. are artificially low," says Andy Xie, former chief economist for Morgan Stanley Asia, who now works independently. "You're not paying the costs of pollution, and that is why China is an environmental catastrophe."

Toxic runoff from China's booming textile industry is one reason why many of the nation's largest rivers resemble open sewers and 300 million people lack access to clean drinking water. Now, U.S. retailers are scrambling to prevent environmental issues from creating the same kind of consumer backlash as the antisweatshop campaigns of the past decade. Fountain Set says it hasn't lost any major customers since the government crackdown, but some U.S. retailers temporarily canceled orders and say they have tightened oversight of the company.

"After labor issues, the environment is the new frontier," says Daryl Brown, vice president for ethics and compliance at Liz Claiborne Inc., which uses Fountain Set cotton in some of its products. "We certainly don't want to be associated with a company that's polluting the waters."

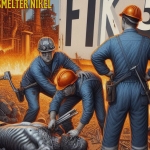

[photo]

The Dongguan Fuan Textiles mill supplies fabric for dozens of U.S. retailers, including Wal-Mart, Gap and Target.

The textile industry is one of China's dirtiest. In addition to heavy metals and various carcinogens, fabric dyes may contain high levels of organic materials, and thread is often dipped in starch before it is woven into fabric. The breakdown of large amounts of organic compounds such as starch can suck all the oxygen out of a river, killing fish, and turning the water into a stagnant sludge.

Fountain Set's 230-acre Dongguan Fuan Textiles factory campus here sends a huge volume of cotton fabric to Americans' closets. The company is the largest knit cotton manufacturer in the world, and its factories are responsible for about 6% of the global supply of knit cotton, according to Eddie Lau, an analyst at Citigroup Inc. in Hong Kong.

Cotton for T-Shirts

The company's main product is the stretchy soft cotton found in T-shirts and sweat shirts sold by companies including Gap Inc., Target Corp. and Eddie Bauer Holdings Inc. Fountain Set also markets a range of eco-friendly fabrics, including organic cotton. The company, listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange, has 20,000 employees. Annual sales topped $900 million last year.

Since the inspection in June of last year, Fountain Set has paid roughly $1.5 million in penalties and spent $2.7 million to upgrade its water-treatment facilities.

"What's happened has happened," says Gordon Yen, executive director of Fountain Set, a native of Hong Kong who studied at Boston University. "What's important is what we did as a company when this was drawn to our attention....When a problem arises, we try to fix it as properly as we can." The company points out that its other two large Chinese mills haven't had similar problems, and the company was in the process of upgrading the Fuan factory waste-water treatment facilities before the government inspection.

The Fuan campus resembles a bustling minicity where bicycles share the streets with forklifts and pallet trucks, and laundry hangs out the windows of worker dormitories. Inside the factory buildings, rows of workers in matching yellow jackets spin cotton thread into billowing sheets of fabric on clacking mechanized knitting machines. On a steamy upper floor, workers in rubber boots dunk the fabric into giant stainless-steel vats of pink and turquoise dye. In gleaming tiled laboratories nearby, workers in white coats run quality checks on finished fabric. One worker tests fabric for colorfastness by dabbing artificial saliva from a beaker onto fabric that will be used in baby clothes.

Plastic file cabinets near the factory floor are labeled with the names of Fountain Set clients, including Gap, Tommy Hilfiger Corp., Reebok and Nike. Nearby, workers at computer stations say they are emailing color samples to companies including Lands' End and Abercrombie & Fitch Co.

A bulletin board displays a certificate from Wal-Mart, stating that the plant is "meeting the color testing methods and performance standards of Wal-Mart Stores Inc." Wal-Mart says the certificate refers only to Fountain Set's machinery and color matching.

Many apparel companies distance themselves from Fountain Set, saying they aren't direct customers, even though they use its fabric. Large retailers typically work directly with Fountain Set to set colors and fabric styles each season, but they may ultimately purchase Fountain Set's products through a third-party supplier that sews the finished goods.

Companies including Target and Liz Claiborne say they have "no contractual relationship" with Fountain Set, but acknowledge they use its products. As recently as June, Fountain Set named Kohl's Corp. of Menomonee Falls, Wis., as one of its customers. In an email statement, Kohl's said it is "not a Fountain Set Holdings client."

Phillips-Van Heusen Corp., which owns brands including Calvin Klein, didn't respond to inquiries for this story. Eddie Bauer Holdings and Tommy Hilfiger Corp. declined to comment.

Fountain Set was founded in Hong Kong in 1969, just as U.S. companies were beginning to seek cheaper production bases in Asia. The initial motive for outsourcing was cheaper labor. But in the early 1970s, stricter environmental laws, such as the 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments, began driving up costs for U.S. fabric mills -- accelerating the overseas shift.

For most of the 20th century, brick textile mills lined the riverbanks of the northeastern U.S., and it was common practice to dump waste water from dyeing directly into rivers. Rivers, such as the Merrimack in New Hampshire, were so polluted they emitted a vile stench, and residents were warned not to swim or fish.

Today, the Merrimack runs clear, and most of the mills along its banks have been shuttered. But much of that pollution has shifted to the East. There's a joke in China today that you can tell what colors are in fashion by looking at the rivers.

Li Changlin, 51 years old, owns a small shipping company along the banks of the Mao Zhou river in Dongguan, downstream from the site where Fountain Sets is accused of dumping.

After two decades of absorbing runoff from hundreds of factories upstream, the river resembles a thick, oily sludge and emits a pungent stench. Its surface is littered with plastic bags, shoes and electrical wires. On a recent day, the carcass of a dog floated near the bank. "We used to eat fish and crayfish out of this river," says Mr. Li, who has lived by the river all his life. "We swam in it. There were green plants on the banks and the water was clear. After 1989, the factories came and the water turned black."

That was the year Fountain Set opened its factory in Dongguan, just as Hong Kong began cracking down on water pollution. Gap, one of the Fuan factory's first American clients, began placing large orders for cotton polo-shirt fabric. Throughout the 1990s, Fountain Set began working with dozens of major retailers and brands, including Wal-Mart, J.C. Penney Co. and Nike.

The rise of discount chain stores, such as Wal-Mart and Target in the mid-1990s, brought intense pressure on fabric mills to keep prices low, according to textile industry executives. "The first thing they say when they sit down in a meeting is, 'How much discount do I get from last year?'" says Bill Lam, former executive director of Fountain Set who is now executive director of a competitor, Pacific Textiles Holdings Ltd.

Discharge Testing

Nike is the only company contacted for this article to provide evidence it monitored the Fuan plant for environmental violations prior to the government crackdown. The plant passed Nike's water-quality inspections every year since 1999. But the testing was voluntary, requiring the factory to submit its own water samples to a lab hired by Nike. In an emailed statement, Nike said that the factory was supposed to be "collecting samples that are representative of the waste water that they typically discharge" but acknowledged "it would be possible to falsify the sample." Fountain Set says the samples it submitted weren't falsified.

Nike says it has stricter environmental-compliance requirements for factories it works with more closely. Since 2000, Nike has developed an advanced factory-monitoring program after the company admitted to unknowingly using child labor in Pakistan.

The crackdown on Fountain Set was part of an increasingly aggressive campaign by China's central government to curb the environmental damage wrought by three decades of industrial expansion. China's Guangdong province, where Fountain Set is located, is a smoggy landscape of smokestacks and eight-lane highways, where some 50,000 factories churn out toys, cellphones and electronics. Here in Dongguan, a major manufacturing center, the air smells of burning rubber. Under pressure from Beijing, provincial officials have been cracking down heavily on polluting industries to encourage greener growth. About 20% to 30% of China's water pollution comes from manufacturing goods that are exported, estimates Mr. Xie, the economist.

After environmental-protection officials launched their stealth inspection in June of last year, authorities accused the Guangdong factory of keeping fake books to hide its illegal discharge, and said the amount of dye in the factory's waste water was 19.5 times the legal limit.

When Chinese newspapers began reporting on the findings, Fountain Set told customers over email that "heavy rains" had led to a slight increase in water discharge, but the plant was operating normally. Several weeks later, the company informed customers that a fine had been issued by environmental-protection authorities. The company cooperated with the government, and dialed back production at the plant to reduce its waste-water output.

Mr. Yen was bombarded with calls. Wal-Mart, which had recently launched a slew of initiatives in the U.S. to show its commitment to the environment, sent a team of inspectors to the plant and canceled all direct orders with the factory until the issues were resolved, according to the company. Lands' End, one of Fountain Set's major customers, says it sent inspectors to the plant and reduced its orders with the company. J.C. Penney says it shifted its orders to other Fountain Set factories. Abercrombie & Fitch held a meeting with management. Target says it began exploring alternative cotton suppliers.

Mr. Yen calls it a "very stressful time," but says the vast majority of the company's customers ultimately stuck with the company. Fountain Set considered appealing the fine, and disputes some of what was reported in state-run media. But ultimately the company decided not to challenge the government. "At the end of the day, we made a decision not to dispute the claim, and worked with the provincial environmental bureau so that we could get back to business," says Mr. Yen.

The complexity of the textile-industry supply chain means fabric mills like Fountain Set often escape tight scrutiny from apparel companies, even though mills are the site of the industry's heaviest environmental damage. Gap, for example, employs a full-time social-responsibility staff of 93 people involved in monitoring 2,000 factories around the world for labor issues and environmental practices. But Fountain Set isn't on the list, because Gap's monitoring program focuses on companies that sew fabric into clothes, rather than mills. Gap says it is exploring the possibility of extending its monitoring programs further back in the supply chain, and has already begun examining the water-use practices at its denim laundries.

Apparel companies say they have the most influence over companies at the end of the supply which they work with directly. "We take the most aggressive action where we have the most leverage," says William Anderson, head of Social and Environmental Affairs Asia Pacific at Adidas Group.

Police Force

Many clothing companies say they are pleased to see the Chinese government taking action. Industry executives say the lack of regulatory enforcement in China has forced the apparel industry to become a police force, a job it is ill-equipped to handle.

Some companies defend their decision to stick with Fountain Set, saying it's typically better to work with a factory on improving standards, rather than ditching them when a violation occurs. L.L. Bean Inc. says it considered cutting ties with Fountain Set but was reassured that the company appeared to be cleaning up its act. "If we felt like there was a better option, we would have left," says Jim Ditzel, vice president of inventory. "It's not a perfect world. Wherever you go, it's probably going on elsewhere."

A few miles west of the Fuan factory, a mill owned by Mr. Lam's Pacific Textiles was recently charged with releasing dye water that turned a local river red. Employees from the Panyu, China, factory tried to conceal the problem by taking boats into the river and dumping dye neutralizer into the water, instantly turning the water back to brown. Chemicals in the neutralizer are toxic, and dead fish floated to the surface of the water. The local television news interviewed villagers complaining that the water would poison their crops.

Mr. Lam admits his workers dumped the neutralizer but speculates that his company was set up by a competitor, who may have paid off temporary workers to cause the spill.

Chinese activists are trying to make the textile supply chain more transparent by connecting the dots between Chinese factories and the multinational companies that buy their products. "We want them to know we're watching from China," says Ma Jun, a prominent Chinese water-pollution activist who has launched a Web site that aggregates data about polluting factories.

Fountain Set's new waste-water treatment facility was certified by the provincial authorities in January. Wal-Mart recently resumed placing orders.

- 204 Manufacturing