The Cows Have Come Home

Earlier this summer in Minnesota, the well-dressed woman walked briskly across the front of the red brick classroom and up to the microphone. The moderator smiled and nodded in her direction. Looking down at her notes, she began. "Good afternoon. Thanks for holding this session. And while we are here in this room discussing this important issue, 200 people in Gering, Nebraska, are looking for new jobs. Their packing plant closed this week because they could not source enough cattle due to the embargo."

Janet Riley, the senior vice-president of public affairs for the American Meat Institute (AMI), was referring to a plant owned by Packerland Packing, a subsidiary of Wisconsin-based Smithfield. The Gering plant processed roughly 320 cattle a day, turning the cows into boxed beef products. But following the May 2003 discovery of mad cow disease across the border in Alberta, a legal challenge by Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund (a small Montana-based advocacy group) caused the United States to impose a ban on Canadian cattle imports, effectively cutting off supplies to the Nebraska plant.

Speaking more slowly, Riley stressed: "Gering is not the first plant, and it won't be the last." She continued, "And that's why I and so many others in this room" - here she lifted one arm over her head and pumped it in the air defiantly - " are wearing these black wristbands, because they are the color of mourning. ... And that's exactly how we feel about our industry. What's happening is tragic."

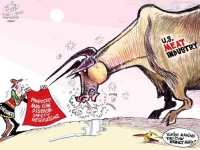

Riley and her colleagues felt that the U. S. beef industry was being held hostage by anti-free trade activists. But in fact, any move to boost protections against mad cow disease -- by health and consumer groups or, less frequently, by U.S. officials -- was invariably dismissed by the AMI as unnecessary, alarmist and harmful.

Beef Lobby

AMI is a major industry group, headquartered in Washington DC, representing "companies that process 70 percent of U.S. meat and poultry and their suppliers throughout America," according to its website. Members include Tyson, Cargill, Hormel, Smithfield, Kraft, Sara Lee and other major players in the $78 billion beef industry (estimated for 2005)..

| Something to Chew On BSE spreads among cattle (and from cattle to humans) via the food supply. In the past, unmarketable cow parts were routinely ground up and fed back to cows. The practice was seen as a win-win situation: live cattle enjoyed a protein-rich diet, helping them grow larger and produce more milk, and previously worthless waste products were turned into valuable feed ingredients. In the mid-1990s, the National Renderers Association even promoted itself as "the original recyclers." After Britain's BSE epidemic revealed the risks inherent in this practice, in 1997 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited most protein from ruminant animals - including cattle, sheep, goats and deer - from being fed to ruminant livestock. From the beginning, however, many criticized the FDA's feed regulations as riddled with loopholes. Consumers Union called them "totally inadequate to protect the public health," because pork, poultry, horsemeat, and even blood and gelatin from ruminant animals, could still be fed to cattle. Pigs, poultry and horses are not known to have their own mad cow-type disease, but pigs can be infected under experimental conditions. And disease transmission via blood, which has been implicated in two vCJD cases in Britain, makes the common practice of weaning calves on milk replacer containing cattle blood protein "a really stupid idea," according to Nobel laureate Dr. Stanley Prusiner. In 2002, Congress' nonpartisan investigative arm, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted, "The United States has a more permissive feed ban than other countries." The GAO also found that the "FDA has not acted promptly to compel firms to keep prohibited proteins out of cattle feed and to label animal feed that cannot be fed to cattle. ... Moreover, FDA's data on inspections are severely flawed and, as a result, FDA does not know the full extent of industry compliance." But it wasn't until the first U.S. case of BSE was discovered - in Washington state on December 23, 2003 - that officials considered doing anything. The following month, then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson said, "Although the current animal feed rule provides a strong barrier against the further spread of BSE, we must never be satisfied with the status quo where the health and safety of our animals and our population is at stake. ... Small as the risk may already be, this is the time to make sure the public is protected to the greatest extent possible." His department put forth proposals to ban mammalian blood and poultry waste from ruminant feed, to ban nervous system and other high-risk cattle tissues from all animal feed, and to require separate production of ruminant and non-ruminant feeds to avoid cross-contamination. But thanks to industry pressure (see article), nearly two years later, the FDA is only now considering taking action. |

The June 9 event Riley addressed was a hastily organized U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) panel discussion led by the Secretary of Agriculture, Mike Johanns. The discussion, titled, "The Safety of North American Beef and the Economic Effect of BSE on the U.S. Beef Industry," was at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

BSE, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, is better known as mad cow disease. And Riley was right about at least one thing - it has tragic consequences. The disease slowly and silently incubates, before emerging to cause marked changes in cows' behavior, often including aggression, motor problems and inevitably death.

If the story ended there, it would be sad instead of tragic - but it doesn't. The disease can spread across species, including to humans. The human version, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), has similar symptoms as BSE, and is also always fatal.

In Britain, the hardest hit country, more than four million cattle were destroyed and 157 people have been diagnosed with vCJD. One hundred and fifty of them, mostly young adults, have since died. The average age of a vCJD victim is 28, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Given the possible consequences, you might expect the AMI and other industry groups and companies trading in beef to advocate for the strongest possible safeguards - including banning all dangerous feeding practices-- especially after the United States confirmed two cases of BSE. (Preliminary announcements regarding the second case were made the day following the USDA panel.)

Instead, the vast majority of these groups have fought against fundamental BSE precautions.

When government officials made some rather feeble attempts to try to protect consumers of U.S. beef -- and, indirectly, the industry itself [see sidebar] -- the AMI and other groups lashed out, calling the proposed reforms "unwarranted." AMI Foundation president James Hodges explained, "BSE prevention strategies must be both scientifically based and economically prudent." He singled out one proposal, to remove high-risk cattle tissues from animal feed, as "fail[ing] both criteria."

In other words, the potential health risk was weighed against industry's bottom line -- and the latter won. The AMI lobbied hard against new regulations. "Producers and processors will be forced to shoulder enormous economic hardships while the government has no real evidence that the steps it's proposing will have any net benefit to anyone," the group claimed in a news release.

To dramatize the impact of the proposed regulations, the AMI estimated that just those tissues at highest risk for transmitting BSE - the spinal cord, brain, skull, backbone, small intestine and tonsils - from all cattle slaughtered in the United States added up to a veritable mountain of 684,000 tons per year.

If this cow offal were banned from being "recycled" into animal feed and other valuable products, it would eliminate $72 million in annual income to the livestock industry, according to the AMI. Moreover, maintaining a high-protein diet for cattle in the absence of these glistening byproducts would require "an additional 5 million bushels of soybeans or 140,000 acres of soybean production." Even worse, the banned cattle tissues would then need to be disposed of, at an estimated cost of $55 million per year - and that's assuming that "landfills will accept slaughter waste and adequate space is available."

The AMI also joined in a joint comment to the FDA, co-signed by other cattle, meat and feed industry trade groups. The comment urged the agency to take its time responding to the appearance of BSE in the United States and stated that any potential new policies "must be evaluated" using a "rigorous cost/benefit analysis." The comment painted such an analysis as key to ensuring "the feasibility, appropriateness, effectiveness of various BSE mitigation techniques" while avoiding unnecessary "opportunity costs and unintended consequences."

Rather than implement the FDA proposals, the comment suggested, "There may be alternative actions that enable the agency, in concert with industry, to create a system of enhanced feed controls providing equivalent risk mitigation. ... All agree removing all [high-risk materials] from animal feed will cause economic dislocation throughout the livestock industry." In addition to the AMI, the signatories to the comment were the American Feed Industry Association, American Sheep Industry Association, National Grain and Feed Association, National Meat Association, National Milk Producers Federation, National Renderers Association, and National Cattlemen's Beef Association.

Ultimately, the AMI and like-minded groups got pretty much what they lobbied for. In mid-2004, the FDA downgraded the status of the proposed new feed regulations, effectively delaying their implementation by several years. Currently, the dangerous offal trade continues, but FDA officials recently vowed to revise the feed regulations "in the next month or two." However, it's unclear how strong the new rules will be, or when they will take affect.

Seats at the Table

It's not surprising that industry groups have been able to shape U.S. government policies on mad cow disease.

The composition of the USDA's June 9 panel discussion in St. Paul provides an accurate picture of who, literally, has a seat at the table. Besides the USDA itself, participants represented the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture, National Meat Association, Ranchers-Cattlemen's Action Legal Fund (R-CALF), American Farm Bureau Federation, National Cattlemen's Beef Association, National Farmer's Union, National Milk Producers Federation, National Renderers Association, and the AMI. Not one health, consumer or animal welfare group was included.

Like other interests, the agribusiness industry uses various channels to obtain and wield its influence. One is the government/industry revolving door, which helps maintain an industry perspective at the highest levels of government. For example, current Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Charles Conner is the former president of the Corn Refiners Association. The USDA's Chief of Staff, Dale Moore, was the National Cattlemen's Beef Association's chief lobbyist for eight years, directly before joining the department. And USDA Chief Information Officer Scott Charbo used to work for a subsidiary of ConAgra.

Another channel of influence is campaign contributions. Nearly 80 percent of the more than $7.1 million in campaign contributions that the livestock and meat processing and products industries made in 2004 went to Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

But contributions aren't the only way industry groups insert themselves into the political process. In August 2004, as the presidential race heated up, the influential National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA) took "historic and unprecedented action in the organization's 106-year history by directing its Political Action Committee to endorse Bush-Cheney for re-election."

Following the unanimous vote to endorse Bush-Cheney, then-NCBA president Jan Lyons said, "As usual, the voice of NCBA cattle producers will be heard loud and clear on Capitol Hill - no matter how many thousands of miles away they are from the beltway." In her fall letter to NCBA members, Lyons elaborated on the endorsement: "Some people wonder why we have never taken such a step before, and why we chose to do so now. To that question, I simply say that never before has the future of our industry been so much at stake."

Lastly, and specifically with regard to mad cow disease, industry groups have influenced the science upon which government policies are based. "Consumer groups were shut out" of the process for developing the Mad Cow Risk Analysis Model that current regulations are based on, reported the Sacramento Bee. But among those acknowledged for "scientific input and support" are people "with ties to ConAgra Beef, the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, the National Renderers Association and the American Feed Industry Association."

Licking Self-inflicted Wounds

The irony is that by these actions, the AMI, NCBA and other groups have helped create the difficulties now facing their own industry.

Although domestic beef consumption has remained high since the discovery of BSE in the United States - thanks to some award-winning PR campaigns - the foreign market for U.S. beef remains a shadow of its former self. According to a Kansas State University study, "total U.S. beef industry losses arising from the loss of beef and offal exports during 2004 ranged from $3.2 billion to $4.7 billion."

As a recent, scathing New York Times editorial noted, "More than 60 countries have completely or partly banned American beef, including Japan, the largest importer." At least some of those overseas markets would resume imports of U.S. beef if more cattle were tested for BSE.

Currently, the USDA tests just over one percent of cattle slaughtered, the vast majority of which are "high risk" animals already routed away from the human food supply. Department officials have frequently stated that their BSE testing program is designed for disease surveillance, not food safety.

But the USDA also forbids private beef producers from offering screened, BSE-free meat to foreign or domestic customers. This testing ban cost the U.S. beef industry $747 million in lost revenue in 2004 alone, the Kansas study estimated, using conservative assumptions.

Why doesn't the USDA allow private BSE testing? According to the Times, "Major slaughterhouses feared that universal testing by [smaller beef producers] would create pressure on them to do the same."

Lastly, the 200 laid-off meatpackers that the AMI's Janet Riley lamented in St. Paul represent just a small fraction of the 7,800 meat processing jobs that have been lost since May 2003, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The AMI blames these job losses on an on-again, off-again and now partial U.S. ban on Canadian beef. Canada has confirmed three BSE positive cattle among its herds; the first was found in May 2003.

Considering that AMI and allied groups resisted precautionary measures, stalled new policies following the first U.S. mad cow case, and opposed private initiatives to improve the international market, it's hard to take the industry's crocodile tears seriously.

In fact, Ms. Riley's black wristband could be seen as signaling a Greek tragedy. Much like the seed of Oedipus' or Macbeth's downfall can be found in the protagonist's own boundless pride, the current troubles facing the beef industry can be attributed to its short-sighted, nearly pathological, opposition to even the smallest decrease in profit margins.

Diane Farsetta is a senior researcher at the Center for Media and Democracy (www.prwatch.org).