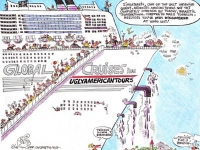

Dark Side of the Tourist Boom: Cruise Ship Controversies Cross Borders

Environmental and community activists in the Mexican Pacific resort of Zihuatanejo recently celebrated the cancellation of a cruise ship terminal that would have accommodated two thousand-foot "floating hotels" at once. Opponents feared a large pier on the town's main beach would contribute to bay pollution and ruin the quirky, small-town atmosphere that attracts return visitors year-after-year. For months, the People in Defense of the Bay coalition had staged protest rallies, posted on-line petitions and fired off letters to government officials - including planners at the federal Ministry of Communications and Transportation (SCT).

Set on Zihuatanejo's main beach, the multi-story Casa Marina was a hotbed of activism. Banners and signs opposing a new pier draped the building that houses locally-owned businesses as well as the Humane Society, where scraggly street cats and spooked pelicans are nursed back to health. Inside the edifice, merchant and green activist Natalia Rodriguez Krebs runs a store that offers eye-grabbing indigenous art, crafts and clothing.

Rodriguez and other locals have long received the cruise ships that anchor inside the bay one at a time, and shuttle passengers in small boats (known as tenders) to the existing pier where they run a gauntlet of day-tour operators. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks on the United States, Mexican marines guarding the municipal pier have joined the throng.

That is not the only influence that Washington's "war on terror" has exerted on this small Mexican town. Since international regulations drafted in the wake of 9/11 mandate that other boats maintain a fixed distance from the cruise ships, industry expansions imply an increasing privatization of public waterways. Hosting ever-bigger cruise ships also means transforming the natural environment and reallocating local resources. Bays are dredged, local water supplies tapped and garbage unloaded. At terminals, walkways are fenced off, access roads expanded for day-tour buses and local businesses sometimes threatened with relocation. Invasive species hitchhiking on the cruise ships can alter local ecosystems.

"To allow the construction of a marine terminal in the middle of Zihuatanejo Bay means the collapse of the town," declared environmentalist Silvestre Pacheco, project director for the SOS Bahia group.

The Business of Cruising

The dynamic that boiled over in Zihuatanejo is simmering in coastal communities across Mexico, the world's Numero Uno cruise destination. The number of ship passengers visiting Mexican waters doubled from about 3.2 million in 2000 to 6.4 million in 2007, according to the Florida Caribbean Cruise Association (FCCA), a trade industry group. Some 22 Mexican ports now host cruise ships, and federal officials plan to make the cruise business even bigger. Sailing to Mexico on vessels departing from California and Florida ports, U.S. and Canadian nationals comprise the vast majority of cruise ship tourists. In recent years, cruise vacations have become trendy. Even readers of the liberal Nation magazine and listeners to Air America are pitched cruises hosted by their favorite corporate-bashing celebrities. In fact, in a prematurely triumphant mood, the center-left radio network plans a three-nation Obama victory cruise after the U.S. presidential election in November to Belize, Mexico and Guatemala.

| Cruise Terminal Mega-Project Cancelled Against great odds and powerful economic forces, the activists in Zihuatanejo have succeeded in fending off an unpopular mega-project - at least for now. |

Earmarking tens of millions of tax dollars for infrastructure

development, the Mexican government justifies its investment splurge as

classic, trickle-down economics: More tourists mean more money, hence

more jobs. The question is at what cost and to whose benefit?

According to Mexico's National Tourism Ministry (Sectur), income from

the industry rose from $201.3 million to $487.5 million between 2000

and 2007. Using bigger numbers than Mexico's federal government, the

FCCA estimated that cruise ships contributed $565 million and created

16,000 jobs in Mexico during 2006.

The cash flow from cruise ships is but a small slice of a vast

international tourism industry that earned Mexico $12.9 billion last

year, and employed about 2.4 million people, according to Sectur.

Two lines, Carnival Cruise Line and Royal Caribbean, are the undisputed

lords of Mexican waters, according to trade industry and media reports.

Although the cruise lines run out of U.S. ports and are traded on the

New York Stock Exchange, the foreign-flagged companies are officially

based abroad and not subject to most U.S. taxes or labor laws. Indeed,

many of the largely unregulated cruise industry's 150,000 workers are

from developing nations. They often sleep in hot, squalid underdecks

and get $10 to $20 for a 10- to 13-hour work day, according to the

International Transport Workers' Federation. Tip earning domestic staff

are paid about $50 a month.

Carnival Corporation enjoyed a pair of good years recently. The

company's worldwide revenues increased from $11.8 billion in 2006 to

$13 billion in 2007, with net income moving up from $2.3 billion to

$2.4 billion during the same period. Royal Caribbean's cut of the

market grew from $5.2 billion to $6.1 billion, although the world's

second largest cruise line watched its net income slip from $633

million to $603 million in the two-year period. Faced with the prospect

of slimmer profit margins because of soaring fuel costs in 2008, the

industry has begun charging passengers fuel surtaxes up to $140,

according to the online publication Cruisecritic.com. Nonetheless, a

vibrant European market and a strong euro favor the industry.

But opposition to the expanding industry is also growing. Billionaire

and Carnival CEO Micky Arison, who is also the principal owner of the

Miami Heat basketball team, was involved with Mexican businessmen in a

controversial plan to build a home port on the Mexican Caribbean Island

of Cozumel several years ago. The proposed port elicited opposition

from environmentalists and hotel owners, and as in Zihuatanejo, the SCT

eventually backed down from the project.

Representing 13 lines, the Florida Caribbean Cruise Association participates in meetings and works with Mexican private sector and government leaders to promote the cruise business. The industry recently clashed with Mexican officials over a proposed per-visitor fee for cruise ship passengers. Proponents argued that the charge would help pay for port infrastructure and maintenance; industry countered that added costs would discourage tourism.

Cruise ship companies operate in a "very competitive market" and look for destinations where they can maximize profits, said FCCA President Michele Page in a recent phone interview. That competition means different rules for different ports. Alaska, for example, has slapped a $50 per-visitor fee for environmental and infrastructure services.

Cruise companies already pay their fair share in Mexico, Paige said, given that docking and nearly a dozen other port fees charged can exceed $30,000 per ship. Additionally, cruise companies spend a combined $400 million every year to market Mexico and the Caribbean, Paige said.

After years of wrangling, the Mexican Congress finally decided to levy a $5 visitor fee for cruise ship tourists.

Roberto Maciel, operations manager for the Port of Acapulco, said the fee was originally scheduled to kick in on June 30 but was postponed until September to give Mexican authorities time to implement a collection system. "They are studying the way to collect this," Maciel said.

"It's something that's breathing down our necks. It's not positive, " said Paige. "Costs are extremely high."

Cruise Ship Inspired Militarization?

Rising cost is only one of the challenges the cruise industry is facing. The Mexican marines who watch over cruise ship passengers in Zihuatanejo and other Mexican ports are stationed in response to fears that terrorists will blow a giant floating duck out of the water.

In the aftermath of 9/11, Mexico quickly mobilized its naval resources to protect foreign-owned cruise lines. According to an official report, Mexican navy personnel provided security to 719 cruise ships in the year following the 9/11 attacks. In 2002, the navy deployed more than 4,000 personnel to conduct 1,907 pier and 804 small boat patrols around bays receiving cruise ships. Some 354 vehicles and 94 boats were used to carry out the security missions. According to the Mexican daily La Jornada, the US Department of Defense helped train 44 Mexican marines in port security and anti-terrorism in fiscal year 2006.

Mexican Navy Secretary Mariano Francisco Saynez told a university forum last year that pressure from Washington sparked the cruise ship patrol duty. "It is known that our neighbor is permanently embroiled in belligerent conflicts and is threatened by terrorism," Admiral Sayenz said, according to the Mexican news service Apro.

In a broader sense, the Mexican navy's protection of cruise ships jibes with the country's participation in the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America, a growing strategic alliance between the U.S., Canada and Mexico that envisions the permanent integration of the economic and security policies of the three North American Free Trade Agreement partners.

Cruise ship watch adds one more task to a Mexican military agenda that now includes everything from immigration crackdowns to drug interdictions to chasing sharks from tourist beaches. In a country where direct military involvement in government decision-making is regarded as taboo, and where the Constitution confines soldiers to their barracks during peace-time, the Mexican armed forces' growing role in public life is unsettling many human rights and pro-democracy activists.

While foreign terrorists have not attacked cruise ships in Mexico, home-grown violence has recently touched some passengers visiting Mexican ports.

Acapulco and Zihuatanejo, especially, were rocked in 2006 and 2007 by narco-violence, including grenade attacks, kidnappings and shoot-outs on public streets.

Interviewed during a surge of violence in early 2006, several cruise ship tourists in Acapulco said they had not been warned of any dangers. Due to security concerns, taxi drivers and tour guides are required to receive training and obtain certification. But lax enforcement of the rules sometimes triggers complaints from tourists about the behavior of "guides" who have been known to leave tourists stranded in a strange part of Acapulco.

Real Dangers to Public Safety

Arguably, the greatest dangers are on the ships, themselves. Heavy drinking, illegal drug consumption and gambling (cruise ships have casinos) can spell trouble. Founded in 2006, the International Cruise Victims (IVC) association has grown into a global organization with hundreds of members in 16 countries. The group has documented dozens of mysterious deaths and persons missing from cruise ships, including at least eight people who disappeared in waters off Mexico from 2004 to 2008. Since many crimes occur in international waters, U.S. authorities have limited jurisdiction.

A shipboard victim who reported a sex or other crime at a Mexican port of call would have almost no chance of seeing the violation prosecuted. More than 90 percent of all crimes in Mexico go unpunished, according to government and media reports.

ICV president Kendall Carver knows first-hand how difficult it is to hold cruise lines accountable. He has tried in vain to find out what happened to his 40-year-old daughter, Mariann Carver, who vanished on August 28, 2004 during an Alaska trip with Celebrity Cruise Lines.

Cruise companies have an inherent conflict-of-interest in seriously investigating mayhem aboard their ships, Carver contended, since word of shipboard crime would undermine cruising's carefree, festive image. And that word is less likely to leak out because the companies employ their own security personnel, answerable to their bosses. "We're not opposed to the cruise line industry," Carver said in a phone interview, "but when a crime occurs we want appropriate action taken."

The ICV has lobbied in Washington, D.C., and Sacramento, California, for the stricter regulation of commercial cruise ships and unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate a 10-point security action plan with the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA).

In May, Carver and Laura Dishman, who said she was raped on a Mexico cruise, testified in Sacramento. "There is no security, there is no law," Dishman said of the cruise lines. "It is a lawless environment." A 2007 report from Royal Caribbean Lines submitted to the U.S. Congress admitted to 273 sex-related incidents, including sexual battery, on its ships from 2003 to 2005. Carver contends the real figure is likely much higher since many victims do not report rapes. "Women who are raped [on cruises] never make the papers," he said.

Backed by environmental, labor, and crime victims' organizations, ICV actively supported a California law requiring cruise ships docking in the state to carry an armed ocean ranger or independent law enforcement officer, not only to safeguard passengers but to ensure compliance with environmental laws.

The legislation passed in the California State Senate in May but died in a State Assembly committee chaired by Jose Solorio, a Democratic Party representative from Orange County, home to numerous cruise line terminals. Observers credited heavy lobbying by CLIA and the Peace Officers Research Association of California for the defeat. Working on behalf of CLIA was the well-known California lobbying firm Aaron Read and Associates. Founded in 1978, the company lists AT&T, Citigroup, Conoco Phillips, Northrop Grumman, San Diego State University and the California Medical Association as among its clients.

According to Carver, cruise lines had threatened to pull out of California ports if the bill passed. "What do they have to hide?" Carver asked. CLIA did not return phone calls seeking comment.

The ICVA hopes for better luck at the federal level. On June 25, following Capitol Hill hearings, Massachusetts Senator John Kerry unveiled the Cruise Vessel Security and Safety Act of 2008. It would mandate improved safety features on ships to prevent passengers from falling overboard, require better reporting of crimes, permit rape victims instant access to the FBI and National Sexual Assault Hotline, improve training for ship crew members, and allow the U.S. Coast Guard access to ships in order to monitor waste water disposal and to act as peace officers.

"It is absolutely appalling that the cruise industry still has not instituted basic reforms so that crimes can be prevented, and if crimes do occur, victims have adequate access to justice," read a statement from California Representative Doris Matsui who introduced a similar bill in the U.S. House. "When a goliath like the cruise industry will not act in the best interest of the customers who are entrusting it with their personal well-being, then Congress has a responsibility to step in and shed some light on the problem."

Testifying in the U.S. Senate, Evelyn Fortier, vice-president of the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, described in painstaking detail the extreme difficulties a cruise ship rape victim would encounter in getting a crime investigated in the United States.

Some Congressional members may have an incentive for going slow on reform. Federal Elections Commission (FEC) data compiled by the non-profit Center for Responsive Politics show a cruise ship industry becoming more politically active. According to the Center, the industry donated $4,743,792 to federal campaigns between 1990 and June 2, 2008, with most of the amount coming after 2000.

The contributions were divided almost equally between Republicans and Democrats. It is important to note the FEC data exclude money invested in state and local races in places where the cruise industry is important, including Hawaii, Alaska, California and Florida.

Washington and Mexico City have a different incentive for regulating the cruise industry. Despite announced crackdowns, news reports document numerous arrests of ship personnel for smuggling drugs and other prohibited substances. The bust map traces a sea-going cocaine highway that begins in South America and veers off to the Caribbean on one side and the Pacific on the other. Port-hopping cruise ships can be ideal smuggling containers for the White Gold.

Crime and insecurity aboard the ships is not a public issue in Mexico, but the situation could change. Until now, cruise ship tourism in Mexican waters has been almost 100 percent foreign, but the SCT is studying the possibility of building home ports to allow affluent Mexican tourists the chance to sail the high seas aboard commercial cruise ships.

For the Mexican government, the cruise ship industry is a winner. In April, the Calderon administration signed a multinational agreement with the governments of Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua aimed at attracting even more cruise ships. A new pro-cruise ship organization uniting the countries could be launched later this year. The goal of the Mesoamerican alliance is to "consolidate the region as the principal destination of cruise ships in the world," said Mexican Tourism Minister Rodolfo Elizondo.

Environmentalists, local activists and communities, as well as passengers and workers may end up losers to the expanding cruise industry.

Research and travel assistance for this article was supported in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

- 104 Globalization

- 116 Human Rights

- 180 Media & Entertainment

- 183 Environment

- 188 Consumerism & Commercialism

- 189 Retail & Mega-Stores

- 190 Natural Resources

- 208 Regulation