Drone, Inc. - K. Embedded in the Kill Chain

At any given time, the U.S. operates some 60 drone combat air patrols consisting of three to four aircraft. Each individual aircraft—typically Predators and Reapers made by General Atomics—has two sets of assigned pilots (known as 18Xs after their numbered Mission Operation Specialty training) and sensor operators (1U0X1s) who typically work out of ground control stations—identical custom-designed trailers that can be packed up and moved easily from base to base and even overseas. The Air Force uses trailers made by General Atomics. Lockheed and Northrop Grumman also build similar trailers for use with other drones.222

The pilots are typically officers with college degrees, but the sensor operators—who manage the video cameras, thermal imaging and radar systems—are commonly between 19 and 25 years old, with no more than a high school education.223 All told a full Predator crew can have as many as 180 individuals and a Global Hawk can have up to 500.224

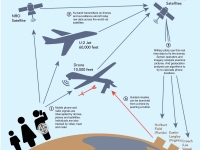

The first set of pilots, the Launch and Recovery Element (LRE), is usually situated a few hundred miles from the target location.225 For Pakistan, they may be positioned in the Kandahar or Jalalabad air base in Afghanistan; for Yemen, in Djibouti or Saudi Arabia. LRE pilots are often contractors from companies like Texas-based Aviation Unmanned, General Atomics, and Merlin Ramco of California.226 Most of them are former Air Force drone pilots, but are paid much higher salaries to work overseas after retirement.

The pilots are accompanied in the field by military and contract radio technicians who manage the satellite data communications. The main contractor is Northrop Grumman, which operates the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) on the ground in countries like Afghanistan, as well as on board piloted aircraft like the Bombardier BD-700.227

LRE crews use C-band transmitters to get the drone into cruising altitude close to the target and then hand over control to the second crew known as the Mission Control Element (MCE).228 One such MCE is the 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing, which manages drones over Ku-band transmitters, working out of identical Ground Control Stations on the other side of the world at Creech Air Force base in Nevada.229

The bigger drones, like Northrop Grumman’s Global Hawk, are managed out of Beale Air Force Base in California, as are Lockheed Martin’s piloted U-2 aircraft.230 Other key positions at these U.S.-based sites are the mission intelligence coordinator and safety observer who keep the drones on task and not crashing.

In addition to the global combat air patrols, managed by the Air Force, the Pentagon has employed contractors in Colombia, Iraq, and former Yugoslavia to operate Florida-based AirScan’s line-of-sight drones.231

The very same surveillance equipment—video cameras, radar and thermal imagers and phone location devices— used on drones are also used on piloted aircraft like Guardrail to complement the drones.232

In Africa, U.S. surveillance relies on humble Cessna and Pilatus turboprop aircraft that carry similar sensors and transmission equipment as Predators and Reapers. They operate out of covert U.S. bases in Arba Minch, Ethiopia; Camp Lemmonier, Djibouti; Nouakchott, Mauritania; Manda Bay, Kenya; Nzara, South Sudan; and Victoria, Seychelles. Pilots from Sierra Nevada Corporation and R-4 Inc. of New Jersey fly the aircraft.233 In the Middle East, the U.S. uses custom-designed Boeing 707s and C-135s like the AWACS, JSTARS, and Rivet Joint that have been conducting surveillance since the 1960s.234 These aircraft do not carry weapons, but sometimes fly high above drones to help them route their signals to satellites. And then there are the U-2 spy planes that fly at 60,000 feet.235

| PTSD One of the biggest hurdles that the drone war faces is the lack of sufficiently trained pilots and analysts. The Air Force recently announced that it graduates only about 180 drone pilots a year, while some 240 of its 1,260 pilots are not expected to continue after their six-year contracts expire.249 When the Government Accountability Office discovered that only about one third of drone pilots had completed their full training before being pressed into service, the Pentagon was forced to cut back on combat air patrols until it could find more properly trained personnel.250 In order to fill these positions more quickly, the Pentagon issued a $100 million contract to CAE of Canada to train 1,500 new pilots at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico; Creech Air Force Base, Nevada; March Air Reserve Base, California; and Hancock Field Air National Guard Base, New York.251 Avwatch of Massachusetts also has a contract to do drone simulation training.252 Meanwhile, since the military is still very short-handed, it routinely has soldiers pull 12-hour shifts, 6 days a week. As a result, Air Force psychological studies have found widespread stress among pilots, analysts, and operators. “What we see are elevated rates of emotional exhaustion and distress,” said Dr. Wayne Chappelle at the School of Aerospace Medicine at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. Stories of the psychological trauma suffered by lower-ranked Air Force personnel are emerging, including several video documentaries: Drone by Tonje Schei, National Bird by Sonia Kennebeck and Unmanned by Robert Greenwald.254 Drone personnel—particularly the low-ranked imagery analysts who watch targets day in and day out—testified that the drone war is deeply inaccurate and disturbing. “How many women and children have you seen incinerated by a Hellfire missile? How many men have you seen crawl across a field, trying to make it to the nearest compound for help while bleeding out from severed legs?” Heather Linebaugh, a former drone imagery analyst, wrote in the Guardian newspaper.255 “When you are exposed to it over and over again it becomes like a small video, embedded in your head, forever on repeat, causing psychological pain and suffering that many people will hopefully never experience.” “It was horrifying to know how easy it was. I felt like a coward because I was halfway across the world, and the guy never even knew I was there,” Bryant told KNPR radio in Nevada. “I felt like I was haunted by a legion of the dead. My physical health was gone, my mental health was crumbled. I was in so much pain I was ready to eat a bullet myself.”256 Even DCGS analysts are reporting higher levels of PTSD and several have committed suicide. “My mental, physical and spiritual health are in the dump. Having an inconsistent, unpredictable and work saturated schedule makes opportunities to improve those near impossible to come by,” one soldier wrote on a Reddit public web forum on DCGS last year.257 |

The video footage streaming via satellite from the drones and piloted aircraft is monitored by imagery analysts from both government and the private sector. Government personnel can be located at bases like Beale or Air Force special operations headquarters in Okaloosa, Florida. Contractors come from a variety of companies including 11 listed by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism: Advanced Concepts Enterprises, BAE Systems, Booz Allen Hamilton, General Dynamics, Intrepid Solutions, L-3 Communications, MacAulay-Brown, SAIC, Transvoyant, Worldwide Language Resources, and Zel Technologies.236

Geolocation of phones is also handled by both government and contractors. BAE and Leidos of California run T/F DOA contracts out of Fort Gordon in Augusta, Georgia.237 Altamira of Virginia also offers Ground Management Target Indicator jobs out of Dayton, Ohio.238

Intelligence analysis is performed by the 480th Wing at Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Hampton, Virginia, which manages DCGS.239 This system integrates significant contractor support from the 70-odd contractors like Modus Operandi that work on different aspects of the software. Individual analysts’ work is coordinated by regionally themed DCGS Analysis & Reporting Teams (DART) teams using software tools developed by Raytheon and Virginia-based NCI.240

The cluttered airspace occupied by drones and piloted planes is managed via the Air Tasking Order (ATO) issued daily by the JFACC (Joint Forces Air Component Commander), while specific data requests are managed via the daily Processing, Exploitation and Dissemination Tasking Order (PTO).241

If the drone operation is backed up by soldiers on the ground, it can access Predator feeds from the DCGS via laptop systems like the Remote Optical Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) made by L-3 for the Air Force or its Army equivalent, the One System Remote Video Terminal (OSRVT) manufactured by AAI Textron.242 Soldiers scattered around the world communicate with each other in text-based chat rooms like the multi-user Internet Relay Chat (mIRC).243

Coordinating the LRE and MCE with ground forces is a Joint Tactical Attack Controller (JTAC) using L-3’s NCCT.244 When a JTAC wants to conduct a strike, they are expected to fill out a “9-line” order that specifies target location and possible friendly forces, etc. Most strikes involve weeks of planning, unless they involve rapid response for an urgent situation such as troops under fire.245 In those instances, the JTAC is expected to fill out a DD Form 1972 which is a more complex version of the 9-line.246 Contractors do not conduct these targeting tasks.

The “floor” Judge Advocate General (JAG) lawyers working out of the Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) monitor compliance with these rules.247 For operations in Central Asia and the Middle East, the lawyers often operate out of Al-Udeid air base in Qatar. They are expected to make sure that strikes meet the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC), the Rules of Engagement (ROE), and the Special Instructions (SPINS) issued for the particular operation. These legal tasks are also not contracted out.248

< Previous • Report Index • Download Report • FAQ/Press Materials • Watch Video • Next >

253

253