A Glittering Demon: Mining, Poverty and Politics in the Democratic Republic of Congo

In the heart of the war-scarred Ituri region in northeastern Congo, some 200 mud-covered men pan for traces of gold in the muddy brown waters.

Working for the Congolese owners of Manyida camp, the miners are following a map of the site made by the Belgians, the country's former colonial rulers.

"It's very difficult, punishing work," says Adamo Bedijo, a 32 year-old university graduate from the central city of Kisangani. "We are not paid, we work until we hit the vein of gold and hope that will pay us...The government has abandoned us, so I am forced to endure all this suffering."

Bedijo is one of Ituri's estimated 70,000 artisanal miners, some of whom are former employees of state mining concerns that collapsed during the country's long-running civil war. Two years after the first democratic elections in 40 years, informal arrangements such as Manyida are operating alongside the many foreign multinationals rushing in to tap the Democratic Republic of Congo's (DRC) extensive mineral resources.

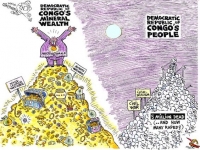

The way foreign multinationals have gained entry into Congo, and the business methods they use, raise significant questions for a nation at historic crossroads. Will the DRC move forward to become more responsive to its nearly 67 million people scattered across an area as large as Western Europe, or will the tradition of rape-as-governance continue?

Autocratic Excesses, Leopold II to Mobutu

Blessed with vast deposits of cobalt, coltan, copper, diamonds and gold, and copiously irrigated by massive rivers, the DRC covers a region spanning Africa's western coast deep into the fecund mountains and miasmic rainforests at its center. Here, the historic Kingdom of Kongo existed in various incarnations for nearly 500 years, encompassing swaths of what is now Angola, Gabon and the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville). By 1877, though, most of what is now the DRC was occupied and ruled as the private fiefdom of Belgium's King Leopold II.

A callous monarch whose forces instituted such practices as chopping off the hands of workers who failed to deliver enough rubber for export, and wiping out whole villages of recalcitrant locals, Leopold's excesses were succeeded in 1908 by the direct rule of Belgium's elected government. Following several chaotic years after independence in 1960, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu seized power in a military coup in 1965 and ruled the nation until his ouster in 1997.

Mirroring aspects of Leopold's rule, Mobutu set up the state as a vehicle for his own political and economic ambitions. He launched a campaign to reduce European influence, which included renaming Congo as Zaire and himself as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga ("The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake"). Nationalizing foreign-held mining interests, Mobutu turned the colonial Société des Mines d'Or de Kilo-Moto Corporation into the Office des Mines d'or de Kilo-Moto (Okimo). Okimo was an immense parastatal company that oversaw mining Ituri's vast gold deposits.

With Mobutu's ouster in 1997, Congo descended into a decade of civil war and upheaval that claimed the lives of more than five million people, according to recent figures from the International Rescue Committee, a relief organization, and that has also spawned an epidemic of rape. Ruling the country from Mobutu's fall until his assassination in 2001, rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila rushed to sign mining deals with multinational corporations to help finance his war against various rebel factions. Though much of the DRC has regained some level of stability following the election of Kabila's son, Joseph, as president in 2006, the east remains tense, with active hostilities in the provinces of North and South Kivu and an apprehensive calm in Ituri itself.

Enter AngloGold Ashanti

The image of the laboring miner is indelibly associated in the DRC with the country's immense and often squandered potential. The nation's 500 franc note depicts a trio of miners prospecting a riverbed. And, in a nation where government title and a gun are often looked on as a right to engage in banditry, mining's glittering potential draws impoverished Congolese and multinational corporations alike.

The company AngloGold Ashanti exemplifies the tensions between moneyed foreign mining firms and local residents following the collapse of the Mobutu dictatorship. Many Congolese expected the new era to bring great dividends. Instead a decade-plus war and the downsizing or closure of state mining concerns cut off the economic lifeblood to far-flung communities.

Formed by a merger of South Africa's AngloGold and Ghana's Ashanti Goldfields corporations in 2003, AngloGold Ashanti is one of the largest mining companies in the world. Before its merger with AngloGold, Ashanti Goldfields purchased interest in a gold mining concession in Ituri that had previously existed as a joint venture between Okimo and Mining Development International. Known as Concession 40, the interest, of which the Congolese government is still the official owner, encompasses a vast swath of 2,000 square kilometers in and around the town of Mongbwalu. It is now under the management of AngloGold Ashanti's local subsidiary, AngloGold Ashanti Kilo (AGK), which began exploration in 2005.

A November 2007 report by a special commission of Congo's Ministry of Mines reviewing mining contracts around the country concluded that the terms and lack of transparency in Ashanti Goldfields original contract violated Congolese law and was thus subject to renegotiation. Signed at the outset of Congo's civil war, the contract was negotiated by three state ministers and Okimo's representatives, none of whose identities were revealed.

Noting that the existing document was "silent on the social clause," obligating AGK to carry out programs to improve the lives of the region's inhabitants, the commission noted that AGK had initiated some local social works. These included rehabilitating a water station and the road between Mogbwalu and Bunia, the provincial capital, as well as maintaining power lines.

But coming after the Okimo years, when the state company not only produced gold but also acted as something of a public welfare office, the change in fortune for Ituri residents has been radical.

Formerly, Okimo employed around 1,700 people and was required to reinvest three percent of its profits in the local community.

"The relationship between AngloGold and the community is not good, there is a lot of difficulty in communication," says Jean-Paul Lonema, a community organizer working for the Mongbwalu branch of the Catholic organization Caritas. "The company's decisions are taken without consulting the population. The population doesn't know anything about the documents AGK signed with the government, they don't know their contents."

Lonema says that the company has refused to divulge the terms of its contract. "We have asked to see this contract many times, especially the articles concerning the possible benefits to the community," he says, noting that, under the Okimo scheme, both the local hospital and technical institute were bankrolled via the mine. "There is a paradox in that there is so much gold here, but the community is still so poor."

Societal Benefit or Corporate Greenwash?

Under the shadow of the now-abandoned Okimo mining laboratory in Mongbwalu, dozens of men stoop in ankle deep chocolate-colored water, sifting to see if they can find anything of value

Andaeko Adia, 47, looks up from the red pail with which he sorts muddy earth. "We are only working to get some food, not to make much money, and sometimes it is not even enough to pay school fees for our children," he says, wiping his hands on his dirt-spattered smock. "Sometimes we work together with our children in order to make some money."

Around 1,500 artisanal miners work the site from 8:00 in the morning until 4:00. When they do find gold, they pay the mine "supervisors" - men who give them the right to work there - 30 percent of whatever they find. They say they sell their gold for around $30 per gram, roughly equivalent to the world market price, and that they have no direct contacts with either Okimo or AGK.

"We were working in Adidi (a now-defunct industrial mine run by Okimo), but AngloGold decided to close the mine," Adia explains. "Now we have started working here, but there is no gold here. They promised to employ us, but they aren't employing us. Our families are really suffering."

AngloGold Ashanti representatives cite the exploratory nature of the company's involvement in the Ituri mine, which will not produce gold until 2011 at the earliest.

"We clearly have a big gap between the expectation of the population after a war period, after the total absence of the state, and the presence of a new company," says Guy-Robert Lukama, the company's country manager for Congo, in his office in the capital, Kinshasa.

"During the previous period, Okimo was not only focused on gold but also made any social development or any sponsorship on behalf of the government," explains Lukama. "It's different for a private company like us...The budget constraints are very huge at this stage."

Lukama's words are echoed by AngloGold Ashanti employees on the ground in Ituri, where the company says it has initiated a dialogue platform with 23 representatives of the community to discuss development issues.

"We're doing exploration, which is a risk operation and we don't have any social obligation according to the DRC mining code. But as AngloGold Ashanti, we have to go together with the community," says Jean-Claude Kanku, community development and relationship manager with AngloGold Ashanti in Mongbwalu. "We have decided to put more money into road building, which has a big impact for the community. It used to take people three days to get to Mongbwalu, now it's three hours. A kilogram of rice used to cost $4, now it's $1.20. It has been a big benefit."

The Ministry of Mines review puts the company's start-up capital at US$18 million. AngloGold Ashanti's yearly budget for social development on the Mongbwalu projects is $150,000, says Kanku.

Conflict in Ituri

Complicating AngolGold Ashanti's presence in Ituri is the legacy of a little-noticed war that shred the region's delicate social fabric. Ituri, like much of Congo, is made up of a patchwork of ethnic and linguistic groups. The dominant tribes in the area have traditionally been the Lendu, a group composed mainly of farmers who arrived from southern Sudan hundreds of years ago, and the Hema, a Nilotic ethnicity that came to the area more recently and devoted themselves to livestock grazing. Other ethnic groups include the Ngiti, who are sometimes associated with the Lendu, and the Gegere, sometimes linked to the Hema.

Despite tensions, the Lendu and Hema had co-existed more or less peacefully, if uneasily, for many years, with Lendu farmers leasing grazing land to Hema herders. This arrangement ended with the arrival of the Belgians in the 1880s. Replicating their policy in Rwanda, which elevated the Tutsi ethnic group over Hutus in the areas of administration, education and business, the Belgians in Congo lavished favors on the Hema, leading to feelings of disenfranchisement and resentment among the Lendu. That imbalance continued under Mobutu, whose nationalization of farmland previously owned by Europeans was overseen by Minister of Agriculture Zbo Kalogi, himself a Hema, who did much to favor his ethnic group.

This volatile brew erupted into open conflict in the region from 1999 until 2007 and claimed at least 60,000 lives. Militias such as the Union des Patriotes Congolais (UPC) claimed to be defending the interests of the Hema and Gegere, while armed factions of the Forces de Résistance Patriotique d'Ituri (FRPI) and the Front Nationaliste et Intégrationniste (FNI) purported to defend the interests of the Lendu and Ngiti. Neighboring powers such as Uganda and Rwanda were only too happy to supply men and armaments to buttress one side against the other in their own quests to control the region's mineral wealth.

All sides in the conflict committed gross human rights abuses. The UPC's November 2002 siege of Mongbwalu, during which it fought alongside forces from future-presidential candidate Jean-Pierre Bemba's Movement Pour la Liberation du Congo, killed at least 200 people, the vast majority civilians. A February 2003 attack on the Hema village of Bogoro by the FRPI killed another 200. Their bones still lie bleaching in the fields outside of town. The next month, the FNI attacked the town of Kilo, directly south of Mongbwalu, during which FNI forces sought to ethnically cleanse the town in a campaign of murder, rape and looting that left more than 100 civilians dead. The FNI eventually succeeded in wresting control of Mongbwalu itself from the UPC by June, at which point it mounted an ethnically-based slaughter of Hema and suspected Hema-sympathizers.

Former FNI leader Mathieu Ngudjolo, former FRPI official Germain Katanga and former UPC head Thomas Lubanga are now imprisoned awaiting trial for war crimes and other charges in the Hague by the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC has also unsealed an indictment against the UPC's Bosco Ntaganda, current the military chief of staff for the Congrès National pour la Défense du People rebel group in Congo's North Kivu province. A fourth militia leader, the FNI's Floribert Njabu, is currently in detention in Kinshasa.

Corporate Connection to Human Rights Abuses?

AngloGold Ashanti's links with the FNI, in particular, in their acquisition of the Mongbwalu concession have been the subject of fierce debate for several years.

It its 2005 report "The Curse of Gold," the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights Watch quotes an unnamed former employee of AngloGold Ashanti stating that Jean-Pierre Bemba, then a vice-president in Congo's transitional government, directed the company to negotiate with the FNI as a means to begin exploratory mining at Mongbwalu. Bemba has denied this charge, and AngloGold Ashanti, in a follow-up letter to Human Rights Watch, contends Bemba's advice was merely an admonition for "the company to continue with its exploration program in the region."

More troubling is an $8,000 payment that AngloGold Ashanti admitted making to the FNI in January 2005. There were also allegations made to Human Rights Watch by an AGK consultant in Mongbwalu and FNI Commander Iribi Pitchou that senior FNI officials used a 4x4 vehicle belonging to the company to traverse Ituri's decaying roads, and also traveled on planes hired by the company to such cities as Beni in the DRC and the Ugandan capital of Kampala.

Alfred Buju, a Catholic priest who heads the Commission Justice et Paix in the provincial capital of Bunia says that the scramble for riches fueled the violence.

"The mining issue has been one of the key issues in the conflict here in Ituri," says Buju.

In the company's June 2005 response to the Human Rights Watch, AngloGold Ashanti writes that "yielding to any form of extortion by an armed militia or anyone else is contrary to the company's principles and values... That there was a breach of this principle in this instance, in that company employees yielded to the militia group FNI's act of extortion, is regretted."

"AngloGold Ashanti does not and will not support militia or any other groups whose actions constitute an assault on efforts to achieve peace and democracy," the company's response continued.

AngloGold Ashanti's conduct in the DRC is not an isolated incident.

In October 2004 in the southern mineral-rich province of Katanga, at least 73 people were killed when Congolese government soldiers raided the town of Kilwa in response to a half-dozen self-declared "rebels" that appeared in the village. A quartet of human rights organizations have charged that Australian company Anvil Mining, the leading copper producer in the DRC, provided logistical support to the army during the siege. Company cars transported bodies of those killed in summary executions and stolen goods looted by soldiers; three of the company's drivers were behind the wheel of Anvil Mining vehicles used during the raid, according to investigators for the United Nations peacekeeping mission in DRC.

Anvil Mining did not respond to requests for comment.

Hopes for a Better Future

Despite past transgression, Alfred Buju says that he thinks there have been improvements in AngloGold Ashanti's behavior, and points to the firm's involvement with PACT, a USAID-funded organization that seeks to encourage business and agricultural development in mining areas. The company argues that, despite widespread poverty in Ituri, synchronization with bodies such as PACT is the only way to bring real progress to the region.

"You cannot develop a country against its people," says AngloGold Ashanti's Guy-Robert Lukama. "You cannot develop a country without a minimum of coordination with all the donors, with other companies, without the relevant authorities on the ground."

In the meantime, the people of Ituri wait expectantly. A traveler comes upon a pair of boys walking down the roadside carrying the telltale shovel and plastic basin that are the tools of the artisanal miners in the region.

"We don't have any other work to do," says one of the boys, Okelo Goge, 12 years old.

"I don't have money, my parents are poor, so I don't go to school," says his companion, who declines to give his name. "This is what we have to do."

Michael Deibert is the author of Notes from the Last Testament: The Struggle for Haiti (Seven Stories Press). He has reported on Africa for a variety of publications since 2007 and served as the correspondent in the Democratic Republic of Congo for the Inter Press Service. His blog can be read at www.michaeldeibert.blogspot.com

- 104 Globalization

- 106 Money & Politics

- 116 Human Rights

- 183 Environment

- 184 Labor

- 185 Corruption

- 208 Regulation