Oil Fuels Suriname-Guyana Border Clash

The humid heat covers you like a blanket when you step from the air-conditioned plane at Guyana's international airport. Even before you reach customs, the boundary between sodden air and damp skin has disappeared. It is not the only border that blurs into vagueness on this remote Northern coast of South America.

Since colonial times, the division between Guyana and neighboring Suriname has been as indistinct and shifting as the haze that settles over it during the rainy season. When Guyana gained its independence from Britain in 1966 and the Dutch cut Suriname loose in 1975, the contested area was the relatively worthless realm of farmers and poor fishermen. But even then, one of Suriname's leaders, Dr. Jaggernath Lachmon, warned the Dutch that giving independence to a country without established borders would generate stacks of problems for future generations. The Dutch, at the independence negotiations, answered that a country, like Suriname with its magnificent poets, would always survive.

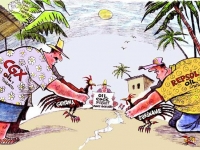

A few decades later, the discovery of vast off-shore oil reserves in the contested territorial waters has fulfilled Lachmon's warning. International corporations-lured by the prospect of an estimated 15 billion barrels of oil-are vying for drilling rights and pushing a centuries' old simmer to the boiling point of open war. Even old sayings have changed. In Suriname it used to be told that "a close neighbor is worth more than a far-flung friend." Now the favored proverb has become: "If things go wrong, your best friend and neighbor may become your biggest foe."

The line between friend and foe runs down the Corantijn River which divides the countries and extends into the sea. The dispute "has spiraled the people of these two countries into an unnecessary conflict and waste of costly time," says Brian Johnson in Guyana who collects taxes and tolls in the Iwokrama nature reservation on one side of the river. On the other bank, customs officer Frank Bruining agrees: "A complete waste of time; these politicians should know better. Instead of cooperating, they fight for political gains at the expense of the common people."

Suriname and Guyana overlap in more than geography: They were both shaped by the immigration trends beginning in the mid 19th century when the abolition of slavery led to settlements and then to overpopulation in urban areas. Later the migration of workers from India, China, and Indonesia created a multi-cultural society and a turbulent political dynamic. And now both countries share a host of social problems intensified by the risks and promises of oil wealth and by the avaricious focus of international corporations jockeying for control.

Border Clash, Corporate Rivalry

Representing Guyana is CGX Energy Inc. of Toronto, Canada. Suriname's claim is being supported by Spain's Repsol YPF of and Denmark's Maersk Oil. And despite moves to try and settle the border dispute though compromise, none of the corporations seem interested in a political solution to the problems.

"Their interest is not ours," says Guyana's Johnson. "Theirs is individual, they have to satisfy their stockholders. Our governments have to feed our people properly and provide us with adequate shelter and sufficient healthcare and schooling."

The international corporations first raised the stakes in 1998 when Guyana granted CGX a concession to drill for oil in the coastal areas it claimed as its own. By 2000 a platform rested over one of Guyana's two promising oil fields. But before drilling started, a Surinamese air force plane spotted the rig and Suriname ordered the it out of what it claims was its territory. Then, in the middle of the night, Surinamese gunboats towed off the Guyana's oil rig and launched a full-scale international crisis.

The Canadians left and waited for further developments. Since then off-shore development by both countries has been stalled while the price of oil and the potential worth of the claims steadily rises.

In February 2004 Guyana, out of peaceful options, took the dispute to the International Tribune of Sea Law in Hamburg, Germany. It accused Suriname of frustrating negotiations the past few years and of provoking trouble when it chased CGX Energy from the disputed sea-area.

Because of procedural rules and bureaucracy regarding communication about the conflict, high officials and attorneys in both countries are not allowed to say much. But both sides charge that it is the other country that is frustrating the bilateral negotiations. Predictions for a ruling range from decades to recent reports from spokespeople in Georgetown and Paramaribo (the capitals of Guyana and Suriname, respectively) that news will break in a few weeks.

Waiting Game

Meanwhile, as the nations and corporations play out the dispute, development is largely on hold, with both countries waiting for future oil wealth.

Suriname, with both oil and other resources is in a better position to wait it out. An almost century-long boom of the bauxite industry catapulted it into one of the more prosperous and affluent countries in the region. Now that exploitation of supplies and resources are reaching their end, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) is looking for prospects in neighboring countries.

And State Oil Company, the pride of Suriname, is a huge and efficient enterprise that generates $70 million annual income for Suriname's 500,000 inhabitants. Managing Director Eddy Jharap runs it like a private corporation rather than with the slow bureaucracy typical of state companies with massive government involvement. State Oil's on-shore drilling in the Saramacca district furnishes the local market with heavy crude and still leaves 25 percent of production for exports. Bauxite and gold also generate income as do developments agreements with the Netherlands.

But none of these enterprises can fund off-shore exploration. "We are unable to do that ourselves," says Jharap. Simply assessing prospects "costs a fortune." In a five-year world-wide assesment ending in 2000, after the U.S. Geological Surveys discovered a potential reserve of 15.3 billion barrels, Repsol quickly chose to do business with Suriname. Maersk and Repsol have agreed to absorb all exploration costs and deduct them from the first income. "Last year we contracted Repsol YPF for the exploration of 12,000 square miles," says Jharap. "And now [we have also signed with] Maersk Oil for another 14,000 square miles. We are very confident."

Earlier, in 1996, Repsol, an extremely active company that moves like a spider in the web of the Caricom and Mercosur countries, also cut an agreement with Guyana.

Guyana is a much poorer country-one of the poorest in South America-and its hopes run high that its deal with CGX Energy Inc. will generate prosperity. CGX Energy and its 62 percent Guyanese subsidiary ON Energy Inc. recently started drilling on-shore in Yakusari region in the first of a four well program.

Warren Workman, vice president of CGX Energy and president of ON Energy, said that the company is embarking on a high risk drilling program based on seismic and geochemical drillings. "It's definitely exciting to finally be drilling the first of our four wildcats," he said. In a wildcat, "an exploratory well in an area not previously know to produce...the probability of a commercial success is very low, typically no better than 10 percent. Over the years in Guyana, there have been only been eight wells drilled on-shore and 11 off-shore; all were dry and abandoned. However, oil and gas shows in several of those historic wells provided evidence of an active hydrocarbon system. A successful outcome would have a significant impact on both our shareholders and the country of Guyana."

Legal Battle

The real prize seems to lie in the disputed off-shore reserves, and the critical dynamic is among big multi-national corporations and now, their lawyers.

Guyana, with few resources and no other peaceful options, has decided to go to the International Tribune of Sea Law in Hamburg. Suriname has hired Professor Hans Smit, a legend at New York's Columbia University and Guyana has turned to Professor Frank Smith (recently retired from the University of Washington). Each has formed high-profile legal teams to bring the case to the international court.

Guyana is accusing Suriname of violating international law of the sea and contending that both countries have signed treaties and conventions dictating a peaceful solution to possible international conflicts. Guyana claims to have suffered financial losses as a result of the military actions of Suriname and demands that Suriname take no further actions against fishermen and others in the contentious region.

Moreover, Guyana demands that Suriname stop developing the disputed sea-area between 10 and 34 degrees, facing the real north measured from a spot on the westbank of the Corantijn River between the two countries.

A legal decision may take up as many as 30 years and even then is not binding.

Given the unalterable fact that none of the land claims are backed by definitive documents, the only sensible option would seem to be for the two countries would exploit the riches together. But with little likelihood of that -especially in light of the role of the corporations' aggressive role in pushing a winner-take-all positions-the courts may be the only hope of avoiding armed hostilities.

Soccer Matches Suspended

The dispute has trickled down to the ground level, where increasingly Guyanese and Surinamese are seeing the other as enemy, rival and scapegoat. Soccer matches between previously friendly clubs are now suspended. Residents of both countries frown on visitors from their neighbor and shun their manufactured products.

Others, in the elites and at the grassroots, are trying to find common ground in a shared history, promise, and problems. In Brasilia, ambassadors for both countries, Marilyn Miles of Guyana and Rajendrakumar Sonny Hira of Suriname remain the best of friends. Ambassador Hira agrees and says that the conflict seems theoretical and should not be carried over into real life. "I love him dearly," says Miles in her office. "The hostility, sometimes felt between the two countries does not exist between the two of us."

Both see the border dispute as an unhappy development and hope for an outcome that benefits the people.

That same hope is maintained by Derryck Ferrier, an American-trained economist and consultant in Suriname. He says that the losers of this quarrel are the middle-class of these both nations who risk falling back into lower levels of society and joining the poor. And without increased prosperity, the poor will have little chance of improving their lot.

"Oil has seldom benefitted the local population," Ferrier told CorpWatch in a telephone conversation. "It is a reason for war and disturbance of peace. Companies do not really care about the environmental hazards they generate. Especially foreign companies. Once they have the oil and leave the countries they do not clean up after them. Look at what happened in Maracaibo, Venezuela or Cubatao, Brazil. People are not able to live and work there any more because of the poisoning of the soil. Foul air pollution makes people who live around refineries sick. There are many more examples from all over the world, from Aceh and East Timor in Indonesia to Chad in Africa and Aruba or Curacao in the Netherlands Antilles."

Ferrier emphasized, "the only thing we can do is hope that our leaders, meeting next month (July) in Grenada, will be sensible enough and make up their minds before its too late and our peoples are turned against each other as a result of companies fueling and pushing towards open hostility that is in no-one's interest but their own."

- 190 Natural Resources