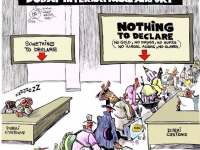

Ports of Profit

Dubai Does Brisk War Business

Every morning, from dawn till about noon, cargo and passenger flights to Iraq and Afghanistan make Dubai airport's Terminal Two possibly the busiest commercial terminal in the world for the "global war of terrorism." Conveniently located between the two countries, Dubai is the ideal hub for military contractors and a lucrative link in the commercial supply chain of goods and people between Afghanistan or Iraq and the rest of the world.

The trade from this relatively small air terminal is completely legal but some of the flight operators have been known to flout the law in order to keep the profitable business going. Tickets to either destination go for about $400 a seat round-trip, cargo travels for about $2 a kilogram.

The European and American travelers arriving at the much larger Terminal One never see this part of the world's second busiest sea/air hub. They are whisked away by banks of gleaming silver escalators to duty-free shopping, sunbathing at the seven star resorts and the famous gold markets.

But at Terminal Two, the most common destinations on the overhead list are Baghdad and Kabul, via airlines like African Express, Al Ishtar, and Jupiter. Most of the passengers on these flights are Afghan or Iraqi, but every morning a few Americans, Indians and Philippinos arrive, often accompanied by minders to make sure that they catch their flights. Some are from the United States embassy or military, others from Halliburton subsidiary, Kellogg, Brown & Root (KBR), the biggest contractor in both countries.

Dubai Ports |

Labor Supply

On Saturday, December 10, 2005, flight XU 106 of African Express airways, officially based in Nairobi, Kenya, was scheduled to take off from Terminal Two in Dubai for Mosul when immigration intercepted 88 Philippino workers. The men had just arrived in Dubai on tourist visas and were ticketed to leave on the early morning flight to northern Iraq.

Officially the Philippine government has banned its nationals from working in Iraq after truck driver Angelo de la Cruz was kidnapped in July 2004. In addition at least six Philippino workers have also been killed while working in Iraq over the last two years. In an attempt to prevent workers from going to Iraq, all new Philippino passports are now stamped with "Not Valid for Travel to Iraq."

Yet some 6,000 Philippinos are estimated to continue to work in Iraq. Some were lured by of the relatively high pay for unskilled jobs; others were forced to take the jobs, according to interviews with workers conducted by CorpWatch.

Some of those detained in December say that they paid a Manila labor recruitment agency, Tierra Mar, between 40,000 to 70,000 pesos each (US$760 to $1330) for the jobs. Arrested with the 88 workers was Jordanian national Mah'd Moh'd Ahmad Hamza who was issued a temporary visitor's visa to the Philippines by the country's consulate in Dubai on September 19, 2005.

The 88 workers were deported back to Manila the following week and Tierra Mar has been placed under investigation for breaking the ban. However, government officials say the incident may just be the tip of the iceberg.

"United Arab Emirates seems to be a favored jump-off point because of the facility in obtaining a visit visa to this country," Philippine Labor Secretary Patricia Santo Tomas, told reporters. "We received information that the modus operandi of those circumventing the government restriction seems to be the use of old passports without the travel ban stamp," she added.

Prime Projects International

One of the key players in the supply of labor to Iraq is located a 20 minute ride from the airport in a skyscraper that overlooks Dubai Creek. Prime Projects International (PPI) is on the fifth floor of the office building of the Twin Towers, behind the dark blue glass windows that reflect the sun as it sets over the ocean in the evening.

PPI was created just months after September 11, 2001 when British businessman Neal Helliwell and his partner, Toby O'Connell, won a subcontract from Halliburton to help construct prisons in Guantanamo Bay for KBR. They kept costs down by using low-wage Philippino labor.

Since then Helliwell and O'Connell have supplied workers to build Camp Anaconda, a U.S. military base in Balad, northern Iraq. They are estimated to supply over 7,000 workers to their clients, many of whom are from the Indian sub-continent or the Philippines.

Indeed on November 10, 2005, Philippines President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, gave a special "International Employer Awards" at Malacanang palace to Neil Helliwell, chief executive officer of PPI. The award was for "displaying continuous preferences for Philippino workers and providing them with excellent career advancement and generous package of employment benefits."

But their workers who have made it into Iraq complain that they have been treated badly. "TCNs (Third Country Nationals) had a lot of problems with overtime and things," recalls Sharon Reynolds of Kirbyville, Texas, who was employed as an administrator by Halliburton. "I remember one time that they didn't get paid for four months."

"They don't get sick pay and if PPI had insurance, they sure didn't talk about it much," Reynolds recalls. "TCNs had a lot of problems with overtime and things. ...I had to go to bat for them to get shoes and proper clothing."

"(They) had to stand in line with plates and were served something like be curry and fish heads from big old pots," Reynolds says incredulously. "It looked like a concentration camp."

(see Blood, Sweat & Tears: Asia's Poor Build U.S. Bases in Iraq)

PPI officials have refused to talk to the media at all but CorpWatch has learned that the company is being monitored by the State department for "human trafficking" of workers into Iraq.

One thing is certain - Helliwell and O'Connell have made good money in this business. In May 2005 the two men bought a yacht named "Pacific 50, Yo!" that they raced off the coast of Thailand on the island of Koh Samui.

Cargo Supply

This January, a month after the Philippino workers were deported from Terminal Two, business is still brisk. Most mornings liaison staff from two companies can be seen at the airport: SkyLink, a Canadian company provides flights for employees, and Eagle Global Logistics (EGL), a Texas company, provides cargo handling services for the company into Iraq. The staff, armed with clipboards and pens, make sure that each passenger and each pallet of goods is safely on its way. And every evening, the liaison officers to greet returnees who touch down from Afghanistan and Iraq in the late afternoon and continue arriving until late into the night.

SkyLink and EGL are the last link in the global supply chain of Iraq-bound goods and people that got to Dubai on better known commercial carriers. The United States military uses Federal Express (FedEx); the German airline Lufthansa recently delivered a dozen armored vehicles to Dubai on one of its cargo planes. A United States military officer, working out of the FedEx office, checks cargo manifests every day at Terminal Two, bypassing the country's national customs staff for sensitive cargo.

Many of the goods also arrive into Dubai by ship into Port Rashid and Jebel Ali, the country's two main ports, which rank among the busiest in the world. Barwil, Inchcape and Maersk, shipping companies from Norway, Britain and Denmark respectively, have major import operations that allow cargo to arrive anonymously into the region.

By contrast, Afghanistan has no sea ports and Iraq has just two: Umm Qasr and Khor az Zubayr, both of which face major operational challenges from years of sanctions and neglect. Even after goods arrive at these ports to be transported by truck into the country, they face substantial security threats from attacks and road-side bombs, not to mention skyrocketing insurance rates.

Dubai's choice as the central hub for war traffic is not accidental. A sleepy Middle Eastern port for centuries, famed for its pearl trade and central location on the spice trade from India to the rest of the world, it became suddenly wealthy with the oil boom of the 1970s like the neighboring nations of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. But the emirate wisely decided to invest its money in developing other businesses, such as tourism (which accounts for about a sixth of the national income) and the import-export business (which accounts for two-thirds).

In the last few years as Dubai has become quite expensive. many companies have moved their bases to Sharjah, the neighboring emirate just 30 kilometers away, where rents are half those of Dubai. Indeed many of the aircraft used at Terminal Two are owned by anonymous and shadowy companies in Sharjah. Some of these aircraft owners like Air Bas have been linked to notorious arms smugglers including Victor Bout. Instead of dealing directly with the U.S. government, these companies rent their planes to middle agencies like Chapman Freeborn and Coyne Air, which in turn provide them to Skylink and EGL.

Phony War Surcharges

This profitable re-export business has recently come under scrutiny for overcharging. Under the sub-contract to Halliburton, EGL has been in charge of shipping military equipment ranging from "armor-plated vehicles to trash bins" from Houston to Dubai en route to Iraq for the last two years. The company uses old Russian cargo workhorses: Antonov 12's that can carry 15 tons and Ilyushin 76's that can carry up to 40 tons

In December 2005, the company announced in a Securities & Exchange Commission filing that it was being investigated over these shipments. The focus of the probe was insurance surcharges added by Christopher Joseph Cahill, the regional vice president of EGL, soon after a rival company's plane was shot down in late 2003 while trying to land at Baghdad airport.

Federal investigators in Texas were informed by a whistleblower that the extra 50 cents per kilogram of cargo that was supposedly imposed by Aerospace Consortium (which supplied aircraft to EGL) were in fact, phony. The charges were added to 379 air cargo shipments costing a total of $13.2 million over several months

Mike Lockhart, an assistant U.S. Attorney General in Beaumont, Texas, told CorpWatch that the investigators subpoenaed EGL, seeking information about the surcharges, and were given a letter from Aerospace Consortium explaining the reason for the charges. The documents "looked very suspicious, not what you would expect to see at all," he said. The charter company was also unable to provide any evidence of the insurance increase.

EGL has since fired Cahill and has offered to pay back the military the $1.14 million in "improper charges" that the auditors estimated had been added to the bill. But the Department of Justice wants the company to pay an additional $2.86 million fine.

Lockhart says that the company may have been aware of the charges all along and did nothing to stop it. "They defend their actions and say they were confused, but is is likely that they knew," he told CorpWatch.

"Cahill recognized an opportunity to unilaterally institute war risk surcharges and thereby increase profits to EGL," court documents stated. Cahill also "knew that he did not have to seek approvals from elsewhere within EGL to add such purported war risk surcharges."

"U.S. taxpayers are asked to carry a significant burden during times of war. But they will not be asked to tolerate merchants of war who seek to profit unlawfully from legitimate wartime expenditures," said Rodger Heaton, U.S. attorney for the Central District of Illinois.

An EGL spokeswoman said Cahill was dismissed when the company learned of the fraud. EGL "feels he should be treated appropriately for those violations" under the law, she added.

But Cahill's attorney Edward Chernoff told the Houston Chronicle that his client wasn't collecting any money for himself from these surcharges. "It was a business decision. He wasn't even getting bonuses from it," Chernoff said.

Cahill, who pleaded guilty in mid-February, is to be sentenced May 26 where he faces up to 10 years in prison and a $5 million fine.

Business As Usual

Meanwhile business at the ports of Dubai remain strong and profitable. Indeed Dubai Ports World, the wealthy state-owned company that controls Jebel Ali, into which most military cargo arrives, has stirred tremendous controversey in the last few days by buying up P&O, a British company, giving it control over six major ports in the United States including New York.

David Phinney and Lee Wang contributed reporting for this article.

- 15 Halliburton