Religious Right Discovers Investment Activism

Bible Thumpers Boycott "Cultural Polluters"

Animated insects crawl across the webpage of the Timothy Plan, a group of conservative Christian investment funds that screen investments using Bible-based standards of political correctness. The bugs top the "hall of shame" -- a list of "cultural polluters" that The Plan deems the worst firms, the ones omitted from its mutual funds to protect investors from these "pesky nuisances."

Wyeth is boycotted for manufacturing birth control pills, Merck & Company for fetal tissue research, Procter & Gamble for donating to Planned Parenthood, Amazon.com for officially recognizing gay and lesbian groups. Walt Disney and Earthlink fail to make the Christian cut.

The Timothy Fund screens out 400-500 similar companies for investment because they undermine "family values" by having some connection to pornography, abortion or contraception, "non-marriage" lifestyles, alcohol, gambling, tobacco, and "vulgar" entertainment.

"Our screens are Biblically based," Terry Covert, general counsel of the Timothy Plan, told CorpWatch. "People can use whatever screens they want. Ours are based on the Scriptures. These are God's words," said Covert.

A picture of Jesus is framed on the wall by Covert's desk in his Winter Park, Florida office. The waiting room features the Ten Commandments, down the hall hangs Noah's Ark. Until recently discontinued, the investment company business cards pictured the Bible with piles of money and the flag-- in full-color. Indeed, the firm's very name comes from St.Timothy. ("But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel." I Timothy 5:8)

The Timothy Plan is part of a religious right financial movement that uses fundamentalist values to push conservative evangelism into corporate suites. A tiny portion of the mutual fund market, these firms have adopted investment tools that religious and secular social liberals pioneered to support socially responsible investing (SRI) of eliminating or screening out investments in unsupportable activities. The conservative groups have added a wrinkle with intertwined campaigns of investment screening, shareholder resolutions, boycotts and letter-writing,

| MRI Funds New Covenant Growth Fund Aquinas Funds: A Catholic group, puts abortion and contraceptives at the top of its screening list. Amana Funds, two Koran-based mutual funds, concentrate on avoiding companies that profit from interest, which Muslims are instructed to avoid. (Palm Beach Post) Camco Investors Fund: An open-end fund that seeks to avoid investing in companies that are principally involved in tobacco, alcoholic beverages, gambling, pornography or abortion. (Bloomberg) Noah Fund: Biblical principles-based investment, recently reorganized making its shareholders shareholders in the Timothy Plan. |

The first socially responsible mutual fund began in 1971, but the phenomenon really took root in the mid-1980s with the movement against companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. But unlike the SRIs, the conservative groups support MRI or "morally responsible" investing. And in contrast to progressive religious groups, the Timothy Plan's analysis of the Scriptures finds no problem with investing in arms-makers or military contractors, or companies with poor environmental records or excessive executive pay.

Sometimes the biblical and the progressive investors do land in the same spot. Both, for example, eschew tobacco investments. The Timothy Plan also opposes firms that use child labor, although it has not developed a formal mechanism for screening them.

For example Wal-Mart became a subject of its ire in 2002, although not necessarily for the anti-union activities that progressives might oppose: Ally was appalled to find displays of Cosmopolitan and Glamour, which he said are the "most blatantly aggressive soft core pornographic magazines in America" and create "a moral slippery slope ... the initiation to hard core pornography, child molestation, bestiality and worse." An August 2002 press release was titled "Timothy Plan Mutual Fund Group Denounces Wal-Mart for "Promotion of Pornography.'"

Arthur Ally, the Timothy Fund's founder, describes himself as a "spirit-filled" Christian who believes in the rapture-the approaching end time when good Christians will rise naked into the air to meet Jesus in Heaven. The rest of humanity (the wicked) will suffer the world's end and Doomsday judgment. But until that rapturous day, a profitable stock portfolio is no sin and neither is involvement in the political process. Ally spent 2004 traveling to churches to urge them to take a greater role in politics.

Ally is well-connected to the right, serving on the board of the Liberty Counsel in Orlando, a litigation group that defends anti-abortion protestors and opposes gay marriage. He is a sometimes-participant in the secretive Council for National Policy (CNP), described by right-wing watcher Skipp Porteous as a "virtual who's who of the hard right."

A former vice president at Wall Street investment bankers Shearson Lehman Brothers, Ally began the Timothy Plan in 1994, as his "ministry," with a single fund for pastors. According to Covert, it now runs nine mutual funds, amounting to investments of $345 million and has grown tenfold in five years.

The Plan's Florida headquarters has a staff of eight, with the portfolio management handled by subcontractors and transfer agents who apply the group's politically conservative prerequisites to buy-and-sell decisions. According to Business Week Online, Timothy's Large/Mid-Cap Value fund "has an average annual return since inception of 5.4%. The front-end load is 5.25% and the expense ratio is 1.5%. In February, its ranking was downgraded to one from two stars by Standard & Poor's." (Five is the highest rating).

"We live in a world that's going to hell in a handbasket on greased skids and nobody can figure out why. We know why. This country was established as one nation under God, on biblical principles," said Ally, "and we've turned our back on the God of the universe."

This mix of Bible thumping and market trading draws a half-dozen like-minded funds. Several participate in the National Association of Christian Financial Consultants. The four-year old Ave Maria Catholic Values Fund (AVEMX) in Michigan has the archbishop of Detroit as its "ecclesiastic advisor"; a five-person policy-setting board that includes ultra-conservative Thomas Monaghan, former chair of Domino's Pizza; and Phyllis Schafly, founder of the Eagle Forum and long-time conservative crusader against the equal rights amendment, abortion, and gays. The fund rejects investments in companies that condone abortion, pornography, and "policies that undermine the sacrament of marriage."

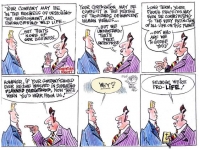

The application of progressive tactics to anti-abortion politics is even more pronounced in shareholder resolution campaigns. The right-wing version emanates largely from Thomas Strohbar in Dayton, Ohio, founder of Pro Vita Advisors. He writes shareholder resolutions for Life Decisions International, an anti-abortion group dedicated to the elimination of Planned Parenthood because it is an abortion provider. "Liberal groups have been doing shareholder resolutions for years," said Strohbar. "I decided to use a familiar tactic, but to apply it to conservative issues, pro-life issues. Usually they've had an impact."

Strohbar proposed his first pro-life resolution in the early 1990s. He was influenced by the progressive groups at the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility in New York that used shareholder resolutions to challenge apartheid in South Africa and push for the cleanup of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Strohbar demanded that AT&T end its donations to Planned Parenthood. As is common, the resolution failed. As is less common, the company complied anyhow, dropping donations to Planned Parenthood in the next year.

"Corporations don't like these things. They are a nuisance, they are a pain in the neck," said Strohbar, a financial adviser who considers his shareholder resolution efforts to be his pro bono work.

Over the years Strohbar has filed 40 resolutions and personally appeared at 20 annual meetings, where the process permits him to make a three to five minute speech. "I get a kick out of it," he said. "I make my little points. You're mandated to be part of the event."

When anti-abortion groups swamp corporations with letters protesting donations to pro-choice causes, Strohbar piles on. "I say, this raises a fiduciary issue for the shareholders. Charitable contributions are supposed to be a matter of goodwill, but look at all the negative letters," he said.

For this reason, Strohbar is particularly fond of companies with retail products. At a General Mills shareowner meeting, he pointed out that anti-abortion letter writers said that they were not going to buy cereal and this boycott was not a good thing for the shareholders. Again, his resolution failed. "Not long thereafter, General Mills, for reasons only they could divine, indicated that they stopped giving to Planned Parenthood," said Strohbar. "They stated that it had nothing to do with the stuff that I mentioned. Of course, that was followed by Target, which did the same thing."

Target said that the company dropped donations to Planned Parenthood in 2000 because of a "shift in focus of our giving," said Carolyn Brookter, Target director of corporate communications. "Planned Parenthood was among probably 250 organizations that no longer receive grants from the Target Foundation."

Learning along the way, Strohbar has filed resolutions at corporate titans: American Express, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, American Home Products, UpJohn/Pharmcia, Kmart, Disney, JP Morgan Chase, Loew's Corporation, Prudential, and, most recently, NCR.

Few elate him so much as his challenge to Omaha-based Berkshire Hathaway, headed by billionaire Warren Buffett. In 2002, Berkshire Hathaway purchased Pampered Chef, one of the largest and fastest-growing kitchenware companies in the US, run mostly by stay-at-home moms who sell the products from their houses. Many of these women were outraged when they discovered that Buffett made charitable donations through the Buffett Foundation to groups that supported abortion as well as those who opposed it.

Anti-abortion activists mounted a Pampered Chef letter-writing campaign, demanding an end to Berkshire Hathaway donations to Planned Parenthood.

To complement these efforts, Strohbar prepared a resolution demanding that Berkshire Hathaway end all corporate donations and delivered it personally at the annual meeting. "Normally, it's a lovefest: 19,500 people show up, they fill the basketball arena. It's preceded by a film on what jovial folks they are. And then they open the business meeting. I had my five minutes; it changed the tone of the meeting," said Strohbar. "I thought I had a snowball's chance in hell. A year later, they did it."

Even though the resolution had only three percent voting support, in July 2003, Berkshire Hathaway announced that because of the Pampered Chef controversy, it was ending corporate donations to all nonprofits--including the Buffett Foundation. Without mentioning Planned Parenthood, Berkshire Hathaway announced that "certain of the donations ... have caused harmful criticism to be directed at Berkshire's new subsidiary, the Pampered Chef [and] ...the careers of many of these consultants are now suffering because of the contributions program," the Chicago Tribune reported.

"The decision is a full-fledged victory," crowed Steve Ertelt on LifeNews.com, a website devoted to pro-life issues.

But Strohbar sees himself as alone in promoting ultra-conservative values though shareholder resolutions. "For better or for worse, no one else is doing it. It gets back to a cultural difference. I don't know how else to explain it," said Strohbar. "It's just a guess, but conservative people are more trusting in corporations, liberals are less trusting."

There's another reason, too: purity. In order to file shareholder resolutions and speak at annual meeting, an individual must own stock in a company for a year or more prior to filing. While the Timothy Plan uses Strohbar's research to screen out companies, it vehemently rejects the notion of buying and holding shares in tainted companies. "God's word says come out from among them and be separate. Don't participate in the evil deeds of darkness," said Ally. "It's not Biblical."

But to a much larger degree, religious right groups do work together to undo support in corporate headquarters for reproductive choice. Twice a year, Life Decisions International, operating from northern Virginia, sells ($15.75) a list of 50-60 anti-abortion boycott targets. LDI is "dedicated to challenging the Culture of Death, concentrating on exposing and fighting the agenda of Planned Parenthood. LDI's chief project is a boycott of corporations that fund the abortion-committing giant," states organization literature. Strohbar is the president of the board.

Current targets, according to LDI's public pronouncements, are the Walt Disney Company (for giving a teen pregnancy prevention grant to a Planned Parenthood affiliate), Adobe Systems, Bank of America, Kenneth Cole, Levi Strauss, Nationwide Insurance, Principal, Prudential, Unilever, Wachovia, Whole Foods, Microsoft, Wyeth, Pfizer, Pantagonia, New York Times, J.P. Morgan Chase, McNeil and Johnson & Johnson. (On its website LDI also lists celebrities who support abortion or Planned Parenthood.)

Life Decisions, in turn, magnifies its reach through the interlocking network of dozens of anti-abortion organizations, websites and news zines, such as LifeNews.com. Its Corporate Funding Project is endorsed by such organizations as Christian Coalition, Concerned Women for America, Family Research Council, Feminists for Life, Eagle Forum, American Family Association, Traditional Values Coalition, American Life League and Human Life International (started with funding by Monaghan). On its advisory committee is Joseph M. Scheidler, national director of the Pro-Life Action League, which organizes in-your-face protests at abortion clinics, now the subject of a case heading to the U.S. Supreme Court.

This combination of groups also encourages and promotes local boycott efforts. Thin Mints, Shortbread Trefoils and other Girl Scout cookies turned into "girl-cotts" for Pro-Life Waco in Texas in 2004. The pro-lifers declared the cookies bannable because the local Girl Scout troop gave a women's recognition award to a Planned Parenthood employee and endorsed a voluntary teen sexuality program. Cookie-sellers were to be shunned. Working closely with an American Life League subdivision, STOPP, Pro-Life Waco headed for the airwaves. Conservative broadcasters pumped the story high, with cookie foes making appearances on the 700 Club on the Christian Broadcasting Network, Bill O'Reilly, Hannity & Combs and Heartland on the Fox Network.

"The Girl Scouts ended that affiliation. We won that confrontation," boasts John Pisciotta, co-director of Pro Life Waco.

But MRI has not won all its battles. Pro Life Waco, for example, failed to generate the same interest this year when it went after the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure, the large Texas-based breast cancer nonprofit. The pro-life group opposed the Komen grant of a mammography machine to a local Planned Parenthood. But Nancy G. Brinker, Komen's founder, is a conservative Bush Pioneer who raised mega-dollars for the president's campaigns and garnered an ambassadorship to Hungary in Bush's first term. The conservative media barely touched the story.

So far, the religious right groups have generated the most corporate heat on anti-choice issues, but gay rights are also in the line of financial fire. In May, the ultra-conservative American Family Association called on its members, claimed at 500,000, to protest Kraft Foods for its agreement to co-sponsor the 2006 Gay Games in Chicago.

Microsoft got caught in the fray this spring, too, after the anti-gay Reverend Ken Hutcherson threatened a boycott. Microsoft at first seemed to capitulate on support for a gay rights bill in Washington State, but when the bill failed by one vote, gay activist employees raised their own cain, and Microsoft's Bill Gates acknowledged the pressure. "We certainly have a lot of employees who sent us mail," he told the Seattle Times. "Next time it comes around that'll be a major factor for us to take into consideration."

The Hutcherson effort, however, points to corporate vulnerability on gay issues.

And Strohbar is on the spot, filing anti-gay shareholder resolutions. His group Pro Vita, is planning to wrok with the Declaration of Alliance, a Virginia group founded by far-right politico Alan Keys to file shareholder resolutions that "highlight homosexual issues in the corporate culture," according to Strohbar.

Already, Strohbar has filed two resolutions. One, against NCR, went to a shareholders annual meeting, where, predictably, it lost, but made a stink, said Strohbar. The other, however, against AT&T was excluded by the Securities and Exchange Commission as not an appropriate subject for a resolution.

Allstate Insurance might want to start looking through SEC files now. According to Strohbar, Allstate commits the sin of giving money to "homosexual rights groups" and inappropriately fired an anti-homosexual employee. "I'm looking for Allstate shareholders now in order to file a resolution," he said.

Religious right investment funds may not occupy a large space on the trading floors of Wall Street. But the research that MRIs support spreads beyond their investors to an extensive network of interlocking right-wing groups. And by pushing a clatter of buzzers at the same time-from investment strategies to shareowner actions, boycotts and noisy protesters--they are being heard in corporate boardrooms and exerting influence that belies their actual financial clout.