Smokestack Injustice? Toxic Texas Smelter May Reopen

The big smokestack's red lights that flash through the night send the unmistakable message that the mothballed smelter is not dead yet. The old American Smelting and Refining Company (Asarco) copper smelter in El Paso, Texas, may have temporarily stopped spewing toxins, but it still unsettles the Paso del Norte borderlands.

Government agencies and environmental groups have blamed the 111-year- old smelter for severe air, soil and groundwater contamination. Nonetheless, on February 13, 2008 the plant was given a new lease on life when the three members of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) voted unanimously to grant Asarco a five-year air quality permit. The vote was a stinging rebuke to hundreds of border residents who had traveled to the state capital of Austin to convince TCEQ to finally shut it down.

The air permit battle is just the latest chapter in the long, controversial history of the Asarco smelter, which is currently owned by a Mexican company. Operating under a series of previous owners the plant processed lead, zinc, silver and copper between 1887 and 1999.

Built close to the banks of the Rio Grande, the smelter sits directly across from working-class neighborhoods and schools in Ciudad Juarez and less than two miles from the low-income, Latino community of Sunland Park, New Mexico. Asarco is also downhill from the University of Texas at El Paso and surrounding middle-class neighborhoods.

The dispute centers around the common, if oversimplified, battle of jobs versus environment. About 100 supporters of reopening the plant turned out for the February 13 meeting wearing blue "Let's Get to Work" T-shirts. Many were former Asarco workers.

Opponents of the smelter included activists from the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, Sierra Club, Sunland Park Grassroots Environmental Group and Ciudad Juarez's Citizens Organized for Integral Community Development. After the TCEQ's decision was announced, protesters rallied outside the agency's Austin offices.

"I knew that they'd rule against us," said Bill Addington, a member of the Rio Grande chapter of the Sierra Club. A long-time opponent of the reopening, he predicted a protracted struggle.

"It took us eight years to stop Sierra Blanca," he said, referring to a proposed nuclear dump.

Nonetheless, public pressure had some effect. The agency wound up granting Asarco a permit for five years instead of the normal 10-year span, and ordered the installation of four air pollution monitors near the plant.

A Century of Jobs and Pollution

For some, the company's two smokestacks, rising hundreds of feet into the air, stand as monuments to the smelter's importance in local history. During its more than a century of operation, the facility

employed upwards of 25,000 workers and offered union jobs in a region defined by low wages and right-to-work laws.

For others, the omnipresent chimneys symbolize an aesthetic, ecological, and economic intrusion. Texas attorney Steve Fisher, a former El Paso neighborhood activist, recalls playing tennis at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) where the kids would

"spit out the sulfur." El Pasoan Rick Provencio, who lived near the smelter during its heyday, remembers "a light-colored taste"

wafting from the hazy sky around Asarco. In neighboring Ciudad Juarez, Martina Contreras blames the smelter for the many throat and nose problems she suffered when the plant was functioning.

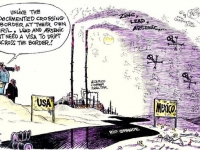

| Bilateral Relations At Risk international agreements. For example, a good neighbor environmental agreement, the 1972 Stockholm Conference, requires participating nations including the United States to not subject other nations to ecologically-harmful activities. environmental side commission, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) of the North American FreeTrade Agreement (NAFTA). The CEC issues statements of findings over the alleged non-enforcement of a member nation's environmental laws, which the Montreal-based agency hopes will carry moral and political weight. |

Asarco has its defenders. A 2007 El Paso Times poll found that

the company's aggressive public relations campaign to reopen the smelter yielded it positive results.

Although a majority of El Pasoans supported reopening the smelter, only a tiny minority of people living closer to the smelter backed such a move.

They were the people most likely to feel the impact of toxic releases. From 1968 to 1971 alone, the smelter belched 1116 tons of lead, 560 tons of zinc, 12 tons of cadmium and 1.2 tons of cancer-causing arsenic into the atmosphere, according to the El Paso City-County Health Office. In those days, travelers heading into El Paso from the west knew they were getting close to the city when thick puffs of black plumes from Asarco's stacks marred the desert vista.

Lead contamination near the plant was so acute that in 1972 Texas health authorities closed down Smeltertown, an Asarco worker settlement. A 1974 public health study by Chihuahua state researchers across the border detected high levels of lead in the blood of Ciudad Juarez children living near Asarco, and it warned that as many as 8,000 children could be at risk. More recently, a 2002 study commissioned by the Chihuahua state legislature found high levels of lead in the blood of more than 200 Ciudad Juarez mothers and their newborn babies. Lead has long been blamed for developmental and learning disabilities in children.

In a 1981 international case, Ontiveros vs. Asarco, Texas lawyers filed a class action lawsuit against Asarco in U.S. District Court on behalf of Ciudad Juarez residents. The plaintiffs included the family of a Mexican child whose death was blamed on toxic poisoning from the smelter. An out-of-court settlement of the case helped divert attention away from Asarco's impact in Ciudad Juarez until more recent years.

Asarco stopped smelting lead in 1985, but continued smelting copper until 1999. By 1993, the company had invested about $100 million in improved pollution control equipment and claimed a 90 percent reduction in emissions.

Modernization Fails?

Despite the modernization, the smelter continued to spew toxic substances into the environment. In 1993, Asarco emitted 253,000 pounds of copper compounds, 27,500 pounds of lead and 28,000 pounds of arsenic, according to a study by the non-profit Texas Center for Policy Studies. Six years later, the smelter's production lines were suspended shortly after the property was acquired by Grupo Mexico.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), New Mexico Environment Department and the U.S. section of the International Boundary and Water Commission all blame the smelter for soil and groundwater contamination near the Asarco plant. A study conducted by award-winning chemist Michael Ketterer for the Sierra Club followed the toxic trail and found a correlation between lead isotopes in contaminated soil in the El Paso area and lead isotopes from the Santa Eulalia, Chihuahua, mine where Asarco once obtained much of its ore.

Although Asarco formally denies responsibility, the company has helped pay for an EPA clean-up program underway since 2002. By late 2007 the federal agency had tested for 24 metals and overseen the removal of soil contaminated with excessive amounts of lead and arsenic from more than 1,000 properties in El Paso and 24 in Sunland Park, New Mexico, according to Jon Rinehart, an EPA official overseeing the clean-up. Mostly, work crews removed dirt from private residences.

Anti-smelter activists are highly critical of the role of environmental regulatory agencies in the Asarco saga. Taylor Moore, a representative of the Sunland Park Grassroots Environmental Group (SPGEG) is quick to point out that both the EPA and New Mexico Environment Department knew about lead contamination in the Sunland Park community of Anapra as far back as 1982, but sat on the problem for years. "The whole exercise is a sham," he says. Not trusting environmental authorities, Moore's group calls for independent testing of Sunland Park's soils. "They're welcome to do that," Rinehart, counters. "The soil we had elevated samples for has been removed."

While contaminated soils have been removed in both El Paso and New Mexico, no clean-up program has so far been carried out in Ciudad Juarez, where the winds of Asarco blew most of the time.

Approved Despite Misgivings

In the long years leading up to TCEQ's decision to allow the smelter to re-open, company boosters emphasized Asarco's role in providing new jobs for a historically depressed economy. In a 2005 Lairy Johnson, Asarco's environmental manager for the El Paso plant, predicted that a revived smelter would add 300-400 jobs.

A 2007 study contracted by Asarco to the Institute for Policy and Economic Development at UTEP went further. It estimated 334 direct jobs, 290 positions in El Paso and 44 at a refinery in Amarillo, Texas, connected to the smelter's operations. A reopened El Paso smelter would indirectly create 1,819 additional jobs and result in an overall economic impact of nearly $1.2 billion, the UTEP study claimed.

Opponents of the reopening insist that potential economic benefits must be weighed against the health and environmental costs.

In February 2008, Erich Birch, an attorney representing the city of El Paso recommended postponing a decision. The EPA, he noted, is in the process of coming up with stricter lead emissions standards than these allowed in Asarco's air permit.

| Who is Grupo Mexico? Headquartered in Mexico City and controlled by the Larrea family, Grupo Mexico is one of the largest mining companies in the world, producing copper, silver, zinc and molybdenum. Chairman and CEO German Larrea has ties to former Mexican President Vicente Fox and former First Lady Martha Sahugan. The Mexican press recently reported that Larrea, whose fortune is estimated at $8 billion, has purchased the Latin American Movie Theaters chain, the second largest operator of movie theaters in Mexico. |

But, on the 13th of that month, TCEQ agreed to allow the smelter to re-open because its emissions fall within permitted state limits under Texas state law despite individual misgivings among commissioners. "If I were king for the day, the Texas Clean Air Act wouldn't look anything like it does today," TCEQ Commissioner Larry Soward told the El Paso Times, after the Austin vote, admitting that he was concerned about the pollution.

While not admitting past pollution, Asarco's current management insists that it has cleaned up its act. It applauded TCEQ's action, stressing how a reopened smelter with modern pollution control technology will be a good corporate citizen.

"Asarco appreciates the privilege of holding a Texas air quality permit and we remain proud to be part of Texas' diverse economy," said Bob Litle, El Paso plant manager, after the vote. Quoted in the Newspaper Tree, an online El Paso media news service, Litle pledged a reborn Asarco would "offer economic prosperity and environmental protection."

In March, the City of El Paso filed a petition with TCEQ asking the agency to revoke Asarco's permission to operate. The petition alleged that Asarco had repeatedly "exceeded state and federal emissions rules." The legal move was also supported by New Mexico Environment Secretary Ron Curry, who charged that TCEQ "looked the other way" when it granted Asarco's permit. Curry vowed to take the necessary steps "to fight that decision."

A response from Asarco lawyer Doug McAllister was posted on the Newspaper Tree website. The petition, he wrote, raised old allegations that had been properly put to rest by the TCEQ's acceptance of Asarco's binational air modeling as well as the state environmental agency's determination that the smelter would not contribute "to a condition of air pollution and will not cause a health threat."

Renewed Attempts to Stop Smelter

Opponents of reopening the smelter are now looking to everything from state regulations to international treaties and agreements to bolster their case, noting that the toxins are not confined to Texas. They point to the fact that testimony in a 2005 public trial in El Paso, held as part of the air permit process for example, revealed that prevailing winds from the smelter blow toward Ciudad Juarez and New Mexico nearly 60 percent of the time.

The activists charge that the air permit decision failed to consider NAFTA, or the La Paz or Stockholm treaties, which are part of U.S. law (see box).

El Paso officials and activists have also charged TCEQ with not enforcing state environmental laws involving Asarco. In El Paso, they cited Asarco's smelting of hazardous wastes from the U.S. Department of Defense's Rocky Mountain Arsenal from 1989 to 1997. According to a General Accountability Office (GAO) report, Asarco proposed recycling wastes from an evaporation pond that was first used by the military in its chemical weapons program, and later by Shell Chemical Company to manufacture agricultural chemicals including pesticides.

The EPA later charged that Asarco violated the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act by shipping and smelting waste without the proper permits. A 1999 consent decree between Asarco and the EPA and other agencies required the company to clean up contamination in El Paso and pay nearly $2 million for the pavement of roads, alleys and parking lots in El Paso. The GAO later reported that Asarco was slow in complying with the agreement.

Details of the hazardous waste chapter were only made public after SPGEG activist Heather McMurray resorted to a state public records law to force TCEQ into releasing a relevant EPA document.

Late last year, El Paso County Attorney José Rodriguez asked TCEQ to look into prosecuting Asarco for illegally incinerating hazardous wastes. But the agency declined to pursue the matter and recently told Rodriguez he could not either.

"This decision clearly illustrates that when a state agency is not given the tools, or does not have the will to investigate and prosecute environmental violations and legal prosecutors are prevented from doing so, the citizens lose and big polluters win," Rodriguez says. "We will continue our fight to correct this imbalance."

Both the EPA and TCEQ discount environmental damage from Asarco's hazardous waste operation. But environmentalists like Bill Addington want more answers and actions. "People have a right to know that hazardous waste was raining down on them," he says.

Smelter Skelter

Further complicating the debate is the issue of who calls the shots for Asarco. Currently, two factions are vying for control of the company assets. Although Asarco is owned by the Mexico City-based Grupo Mexico (see box), the company is presently embroiled in Texas bankruptcy proceedings and temporarily controlled by an independent board of court-appointed directors.

Grupo Mexico's side recently issued a statement pledging that if the corporate parent wrests back management authority, the company will not reopen the El Paso smelter and will to work with authorities and residents to clean up any site contamination. Accusing the independent board of attempting to auction off Asarco's assets, Grupo Mexico blames other board members for delaying Asarco's reorganization.

But Thomas Aldrich, Asarco's vice-president of environmental affairs, considers the El Paso facility a "valuable asset" that could be put to good work in a very profitable global copper market. Asarco management did not respond to reports that outside buyers are interested in acquiring the El Paso property.

Whatever happens, the contamination will endure for a long time. Experts estimate that a thorough clean-up of Asarco's contamination in the Paso del Norte could reach $500 million.

- 116 Human Rights

- 182 Health

- 183 Environment

- 204 Manufacturing

- 208 Regulation