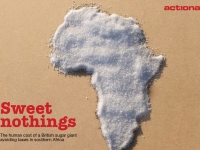

Sweet Nothing: UK Food Giant Avoids Taxes on Zambia Sugar

Associated British Foods (ABF), a UK company that makes

Silver Spoon sugar, pays almost no taxes on its profitable Zambian sugar

subsidiary, according to a new ActionAid report. The authors allege ABF has avoided estimated

taxes of $27 million since 2007, enough to put 48,000 Zambian

children in school.

Zambia Sugar, which owns the Nakambala Sugar plantation in the Mazabuka district of the southern African country, is a subsidiary of Illovo Sugar Limited which is part of "a complicated nest of intermediate companies in Mauritius, Ireland, the Netherlands and Jersey" that is ultimately owned by ABF, according to ActionAid's "Sweet Nothings" report.

The company generates a healthy revenue of some $200 million a year and $18 million in profits. The Guardian newspaper notes that George Weston, the ABF CEO, makes £918,000 a year plus an annual bonus of £864,000 (a total of $2.85 million a year).

On the other hand, Isaac Banda, a seasonal sugar planter for Zambia Sugar, makes just $440 a month, according to ActionAid, less than the estimated $700 that his family of six needs to spend to survive.

Banda actually makes more than most in Zambia, which ranks 164th out of 187 countries surveyed in the United Nations Human Development Report. Two out of every three people live on less than $2 a day and 45 percent of children are malnourished.

"Our school has no windows, doors or floors," says George Sumatama, headmaster of Nakambala school, close to the Zambia Sugar plantation. "Over a thousand children have to fit into just 12 classrooms, sitting in shifts and taught by 20 teachers."

Poor Zambians rely on such schools which are supported by government tax revenues, but unfortunately, ABF's Zambian subsidiary has paid less than 0.5 percent of its pre-tax profits in corporate income tax in the last five years. Indeed ABF even took the government to court to win a special refund of tax paid in earlier years by claiming that its income was from farming rather than manufacturing, despite the fact that the company's principal business is processing sugar it buys from independent farmers.

One way ABF avoids taxes is by contracting out some of Zambia Sugar "purchasing and management" functions to a company in Dublin, Ireland, which happens to benefit from a bilateral treaty that allows cash flows between the two countries to be tax free. ABF also contracts out "trade contacts with customers in the European sugar market,

transportation of sugar to Europe, foreign currency management and the

availability of cost effective credit terms" to a company in Mauritius which in turn is a subsidiary of a South African company where tax rates are lower than in Zambia.

Oddly enough the Irish company has no employees on paper while the company in Mauritius has only one employee.

Meanwhile Zambia Sugar profits are paid out to a Dutch company which in turn allows it to pay significantly lower taxes under yet another bilateral treaty, according to ActionAid.

In one particularly egregious case, Zambia Sugar borrowed money from a

Zambian bank to finance an expansion, but by diverting the loan through

an Irish subsidiary, was able to avoid paying taxes on the interest.

"We do not allege that any of the companies in this report have done anything illegal," write the authors of the ActionAid report. "Indeed, sadly their tax practices are not even particularly unusual. A growing litany of examples from Europe and North America suggest that the arrangements we describe here are simply 'plain vanilla' business practice for many multinationals."

"International corporate tax avoidance is like a cancer eating away at both rich and poor countries," says Chris Jordan, a tax specialist at ActionAid and a co-author of the report. "We know that business can be a force for good in Africa, but this is massively undermined when a company doesn't pay its fair share of tax."

"I think companies operating in Zambia should be paying more (tax) than they currently pay," adds Sumatama, the local school headmaster.

In an official response to the ActionAid report, ABF has issued a statement on its website in which it "denies emphatically that it is engaged in anything illegal, immoral or in any way designed to reduce the tax rightly payable to the Zambian government" which enumerated how much it contributed to Zambia by way of jobs and taxes.

ActionAid says that the company statement is misleading. "None of (AB Foods') arguments seem to stack up or tell the whole story," Chris Jordan told Reuters.

Official government estimates suggest that Zambia loses $2 billion a year to tax avoidance schemes, a substantial sum in a country with a gross domestic product of $20 billion.

Not that Zambia is alone in not being able to collect taxes. The UK has similar problems with foreign companies operating in the country. For example, Starbucks, the Seattle-based international coffee chain, has been accused of tax avoidance in the UK. Between 1998 and 2011 the company has made £3 billion ($4.8 billion) in sales but paid out just £8.6 million ($13.75 million) in taxes on its 735 stores in the country. In the last three years Starbuck did not pay a penny in taxes in the UK.

All told Her Majesty's Revenue & Customs (HMRC) estimates a total of £32 billion ($51.2 billion) was lost to tax avoidance in the UK in 2011 alone, out of a gross domestic product of $2.5 trillion.

- 185 Corruption