US: E-waste dump of the world

When discarded computers vanish from desktops around the world, they often end up in Guiyu, which may be the electronic-waste capital of the globe.

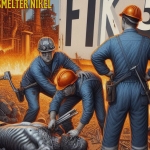

The city is a sprawling computer slaughterhouse. Some 60,000 laborers toil here at primitive e-waste recycling ââ¬" if it can be called that ââ¬" even as the work imperils their health amid a runoff of toxic metals and acids.

Computer carcasses line the streets, awaiting dismemberment. Circuit boards and hard drives lie in huge mounds. At thousands of workshops, laborers shred and grind plastic casings into particles, snip cables and pry chips from circuit boards. Workers pass the boards through red-hot kilns or acid baths to dissolve lead, silver and other metals from the digital detritus. The acrid smell of burning solder and melting plastic fills the air.

Scavenging, not recycling

"I don't think this is recycling," said Wu Song, an environmental activist from nearby Shantou University. "They ignore the environment."

What occurs is more akin to e-waste scavenging. Though China bans imports of electronic waste, its factories clamor for raw materials, even those yanked from the guts of discarded computers, and ill-informed workers seek out computer-recycling jobs. So the ban is ignored, and the waste comes in torrents. Under the guise of "recycling," U.S. e-waste brokers ship discarded computers and dump an environmental problem on China.

In the United States, consumers, manufacturers and retailers are only beginning to heed the cost of safely ending the lives of electronics.

By next year, obsolete computers amassed in the United States will number 500 million, according to the U.S. National Safety Council.

"People just don't know what to do with them," said Jim Puckett, the coordinator of the Basel Action Network, a Seattle-based group that advises consumers about sustainable methods to dispose of e-waste.

Hewlett-Packard of Palo Alto, Calif., committed this year to eliminate a range of hazardous chemicals from its products and has helped lobby for state laws requiring manufacturers to take back old equipment.

Still, a lot of e-waste from the United States continues to seep into China and West Africa, where corruption is extensive and smuggling rampant.

Few restrictions

The U.S. government doesn't ban, or even monitor, e-waste exports.

What's more, the Environmental Protection Agency has no certification process for electronic-waste recyclers. Any company can claim it recycles waste, even if all it does is export it.

Guiyu, a few hours' drive northeast of Hong Kong, is by far China's biggest e-waste scrap heap. The city has 21 villages with 5,500 family workshops handling e-waste. According to the local government Web site, city businesses process 1.5 million tons of e-waste a year, pulling in $75 million in revenue. As much as 80 percent of it comes from overseas.

City officials are proud of the e-waste industry but sensitive about its reputation as a dirty business that feeds off smuggled waste and abuses workers. Journalists who probe quickly find themselves detained by local thugs or police, and their digital photographs or video footage erased.

Local bosses pay little regard to workers' health or to regulations that prohibit dumping acid baths into rivers and venting toxic fumes.

In one district of Guiyu, a migrant worker stood amid piles of capacitors and small circuit boards as fellow workers with pliers tore off soldered metal parts and burned electronic components over braziers to determine their content.

"If you burn it, you can tell what kind of plastic it is," said the man, who gave only his surname, Wang. "They smell different. There are many kinds of plastic, probably 60 or 70 types."

Six of Guiyu's villages specialize in circuit-board disassembly, seven in plastics and metals reprocessing, and two in wire and cable disassembly.

An average computer yields only $1.50 to $2 worth of commodities such as shredded plastic, copper and aluminum, according to a report in November by the Government Accountability Office, a watchdog arm of Congress.

E-waste recyclers in the United States can't cover their costs with such low yields, especially while respecting environmental regulations. So they charge an average of 50 cents a pound for taking in old computers, about $20 to $28 per unit. At that price, experts say, recycling can be done safely and profitably.

But some then ship e-waste abroad for greater profits.

"Up to 80 percent of all obsolete electronics that get collected ends up getting exported," said Ted Smith, the founder of the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition and a director of the national Computer Take Back Campaign, which advocates safe domestic recycling of discarded electronics and directs consumers to recyclers that pledge to use environmental best practices and not to export e-waste.

The flow of U.S. e-waste abroad "is not diminishing," he said. "If anything, it is increasing."

Exporters blamed

Policymakers in Beijing are unhappy about the flow, and blame the exporting countries as much as local dealers and officials in Guiyu and Taizhou, another Chinese e-waste hub.

"The biggest responsibility lies in the developed countries that export e-waste," said Zhang Tianzhu, a professor in the school of environmental engineering at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Zhang, who's advising experts who are drafting a national law on recycling businesses, said China's central government wanted environmentally safe procedures, but "existing e-waste businesses are so large that they are major sources of revenue for local residents and the local government."

Taxes on e-waste businesses provide Guiyu with 90 percent of its commercial and industrial taxes, making officials reluctant to regulate them at all.

The environmental group Greenpeace sampled dust, soil, river sediment and groundwater a year ago in Guiyu and at a site in India where e-waste recycling is done and found soaring levels of toxic heavy metals and organic contaminants in both places.

The group found "over 10 poisonous metals, such as lead, mercury and cadmium, in Guiyu town," said Lai Yun, a campaigner for the group.

When the workers shatter the circuit boards into powder, they rinse it away with water, said Wu, the environmental activist. "And the water goes into the rivers," Wu said. "They also use acid baths to dissolve metals on the boards. The acid is also released into the rivers."

Toxicity is only one reason that recycling electronics is costly in the United States. Another is poor design. U.S. manufacturers haven't made products to facilitate disassembly. The GAO report found that $1 more in design costs per computer could save $4 for American recyclers in disassembly costs. Nor have manufacturers gone very far in finding "green" materials to replace toxic flame retardants.

The lowest bid

The computers that large U.S. institutions and businesses use have a life span of about three years. Old computers are auctioned off to brokers.

"When you're a cash-strapped school system, you're going to go to the lowest bidder," said Puckett of the Basel Action Network. "The lowest bidders are the ones who are going to export."

Many of the discards end up in Guiyu, where workers who earn about $100 a month sort, disassemble, smash, burn and melt them down.

Even if e-waste imports dried up, Guiyu's recycling wouldn't go out of business. China is generating more of its own e-waste.

Last year, vendors sold 20 million computers in China. Within two years, the country will be buying 30 million computers a year, according to a research firm that's associated with the Ministry of Information Industry.

- 195 Chemicals