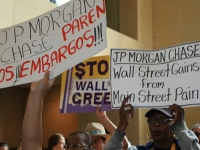

Wall Street Giants - JP Morgan and SAC - Hauled Up On Fraud Allegations

JP Morgan - the Wall Street investment bank - and SAC - a major hedge fund - were hauled up Friday for alleged fraud. JP Morgan was questioned at a U.S. Senate hearing about hiding trading losses while SAC agreed to pay $614 million to settle insider trading charges.

The Wall Street bank attracted Congressional interest because of a $6.2 billion loss that the company incurred last year when a trader named Bruno Iksil - nicknamed the London Whale because of the size of his financial bets - was outsmarted by a hedge fund. (See "Whale Wars: Hedge Funds Rob Banks, and the Poor Suffer Most" on CorpWatch) On Friday the company was forced to testify about how that happened after a damning Senate investigation showed that the company ignored its own risk rules, rewrote key documents and hid information from regulators.

Notably JP Morgan took federally-insured money and used it to construct a $157 billion portfolio of synthetic credit derivatives which they proceeded to gamble with. As the portfolio started to lose money, the panicked traders substituted mid-point valuations that looked more favorable.

"Chase decided to go into the fiction business and invent a new way to value its crazy-ass derivative bets, using, among other things, a computerized model the company designed itself called "P&L predict" which subjectively calculated the value of the entire fund toward the end of every business day," writes the always succinct Matt Taibbi of Rolling Stone. "If this all sounds familiar, it's because it's the same story we've heard over and over again in the financial-scandal era, from Enron to WorldCom to Lehman Brothers - when the going gets tough, and huge companies start to lose money, they change their own accounting methodologies to hide their screw-ups, passing the buck over and over again until the mess explodes into the public's lap."

"The (federal investigators) told the Subcommittee that if the Synthetic Credit Portfolio were an airplane, then the risk metrics were the flight instruments," wrote the Senate investigators. "In the first quarter of 2012, those flight instruments began flashing red and sounding alarms, but rather than change course, JPMorgan Chase personnel disregarded, discounted, or questioned the accuracy of the instruments instead."

There is clear evidence that the federal authorities failed in their oversight duties of these risks, according to the Senate. While JP Morgan misled the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) by not reporting the increase in the size of the portfolio, it did provide numbers that showed that the bank "repeatedly breached the its stress limits in the first half of 2011, triggering them eight times, on occasion for weeks at a stretch." Yet nobody at the OCC appear to notice. (Later, in April 2012, risk limits were exceeded a remarkable 160 times!)

Somewhat surprisingly the person who comes through as clear-sighted is the London Whale himself. Iksil - according to the Senate report - repeatedly tried to warn his bosses about the problems but was ignored.

"I know that you have a problem; you want to be at peace with yourself. It's ok, Bruno, ok, it's alright. I know that you are in a hard position here," Javier Martin-Artajo, one of Iksil's bosses told him at the time.

A key witness at Friday's hearing conducted by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs was Ina Drew, the former head of the chief investment office in charge of trading in London. "Things went terribly wrong," she said, blaming traders like Iksil, claiming that key facts "were not brought to my attention at the time."

"Drew, however, was one of the villains in the bank's own account of what went wrong, and you could see the pressure building up in her mind as she declined to answer, paused, or claimed lack of recall," writes Heidi Moore at the Guardian who watched the Friday hearing. "When Drew was asked if she knew one key and obvious fact - whether JP Morgan had skipped a crucial yearly check on its trading limits - she demurred that she couldn't recall."

Not only did senior management claim that they had no memory of these problems, they did not mention the accounting changes in an internal bank investigation completed in January 2013. "I don't believe we called that out in the report," Michael Cavanagh, co-C.E.O. of JPMorgan's corporate and investment bank, told the hearing.

Senators were furious. "Firing a few traders and their bosses won't be enough to staunch Wall Street's insatiable appetite for risky derivative bets or to stop the excesses," said Carl Levin, the chair of the subcommittee. "When Wall Street plays with fire, American families get burned. The task of federal regulators, and of this Congress, is to take away the matches. The whale trades demonstrate that task is far from complete."

Meanwhile, also in Washington DC, the Securities and Exchange Commission announced that a major hedge fund had agreed to pay $614 million to settle charges of insider trading.

SAC Capital - one of the most profitable hedge funds in history with $15 billion in assets averaging 30 percent in annual profits for 20 years running - has been under investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for several years. (See "U.S. Prosecutors Build Case Against Steve Cohen, Hedge Fund Billionaire")

Most of the settlement related to the case of Mathew Martoma of CR Intrinsic Investors (a SAC subsidiary) who approached Dr. Sidney Gilman, then a 73 year old professor at the University of Michigan, for information on a clinical trial for an Alzheimer's drug being jointly developed by two pharmaceutical companies.

At the time Gilman was chairman of a board monitoring trials of the drug. He was persuaded to sell SAC inside information ahead of time that allowed the investors to avoid $276 million in losses by selling stock as soon as they learned that the drug trials were going badly.

SAC Capital agreed to pay $600 million to settle the Martoma case, without acknowledging any responsibility. But the SEC was blunt about the reason. "The historic monetary sanctions against CR Intrinsic and its affiliates are sharp warning that the SEC will hold hedge fund advisory firms and their funds accountable when employees break the law to benefit the firm," said George Canellos, acting director of the SEC's enforcement division.

In addition SAC also paid out $14 million to the SEC to settle charges against Sigma Capital Management for allegedly profiting from early information about the earnings of Dell and Nvidia, two technology companies.

- 185 Corruption