H&M Responds Slowly to Bangladesh Factory Collapse Killing 1,100

H&M (Hennes & Mauritz), a major Swedish "fast fashion" retailer, led 30 international companies this week to commit to a new $3 billion fund to improve the safety of garment factories in Bangladesh. Watchdog organizations say the companies acted only because of external pressure by activists and workers.

The announcement came weeks after Rana Plaza, a building that housed five garment factories, collapsed in Bangladesh last month leaving over 1,100 dead. While H&M was not among the many international buyers that were found to have contracts with the factories, the disaster sparked an activist campaign that put an enormous amount of pressure on the company which is the second biggest garment retailer in the world and the biggest buyer of clothes from Bangladesh.

Changes in labor and safety practices generally occur "not for philanthropic reasons but because protests were starting to disturb the supply chain" Nayla Ajaltouni, coordinator of the French branch of Clean Clothes Campaign told Agence France Press after riots in Bangladesh in 2010 led to an increase in the minimum wage there. Two years later the story is still the same.

Responding to Disaster

In the days following the Rana Plaza collapse, even as emergency workers dug bodies out of the rubble and families of missing workers fought police in heated street demonstrations, the Walt Disney company, which sources production of toys and clothes from low wage countries around the world, announced it was planning to leave Bangladesh by March 2014.

But H&M said it had no plans to move.

Hanging in the balance are the jobs of over four million workers in Bangladesh who depend on the $20 billion garment industry for their living. The company had the tacit support of many labor organizers who want companies that source from Bangladesh to become more responsible.

"We want buyers to stay and use their power to ensure factories treat workers decently," says Kalpona Akter, an organizer with the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity.

H&M's decision to stay is not entirely altruistic: after all Bangladesh has the world's lowest minimum wage - $38 a month. Safety is a major concern: Clean Clothes Campaign estimates that more than 500 garment workers died on the job between 2006 and 2012.

One reason, say union organizers, is that corrupt government officials tended to look the other way during safety inspections, especially since many senior politicians own garment factories themselves.

To address these issues, Bangladeshi and international unions came up with a proposal titled the "Accord on Fire and Building Safety" that they brought to global retailers, suppliers, NGOs, unionists and government officials at a meeting in Dhaka during April 2011. Intended to be a legally enforceable agreement between retailers, unions and suppliers, it promised a total of $3 billion to fund an independent monitoring body that would oversee all of Bangladesh's 5,000 factories. If a factory did not meet certain standards, it could be shut down.

Two years ago, the plan was wildly unpopular. When the unions pushed it, Walmart's representative shot it down. "It is not financially feasible for the brands to make such investments," Walmart's spokesperson said, according to the meeting minutes.

H&M, the Gap and other retailers also attended the meeting. All of the big brands and factories all walked away without signing the agreement, said Amirul Haque Amin, president of the National Garment Workers Federation in Bangladesh.

A Change of Heart

After the Rana Plaza collapse, the unions' stalemated safety plan suddenly gained traction as public outcry over the deaths mounted. Avaaz, a progressive global campaign group, collected almost one million signatures to pressure H&M and the Gap to sign the agreement.

Initially H&M did not respond.

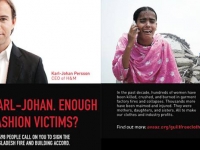

Avaaz then racheted up the pressure - it launched an ad campaign featuring a photo of Karl-Johan Persson, CEO of H&M, alongside a young Bangladeshi woman in tears.

The ad asked the CEOs of H&M and the Gap to take personal responsibility for the deaths of the Bangladeshi workers. "These factories aren't sweatshops, they're deathshops. Hundreds of women have been crushed to death making our clothes," Avaaz said in a May 9 press release. "Two major clothing companies have signed the robust safety agreement, including PVH -- the owner of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger -- but GAP and H&M have yet to state their positions."

Both Dagens Industri, a Swedish newspaper, and Women's Wear Daily magazine, a major industry publication, refused to run the ad, says Avaaz. But as a signature campaign started to get hundreds of thousands of signatures on Facebook, H&M caved and announced it would adopt the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh.

"Our strong presence in Bangladesh gives us the opportunity to contribute to the improvement of the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and contribute to the community's development," Helena Helmersson, an H&M spokesperson, claimed in a press release. "By being on site, put demands on manufacturers and work for continuous improvements, we can slowly but surely contribute to lasting changes."

The company immediately received accolades in the press for "setting an example" and for making a "game-changing" move.

(It should be noted that while H&M has committed to pay a maximum of €500,000 ($640,000) a year into the new building fund, the figure represents a little less than 0.02 percent of the $2.7 billion in profits the company made last year)

Cambodia Victory

This is not the first time that H&M has agreed to change its ways as a result of unwelcome activist attention.

For example, Cambodia is often promoted as an alternative to Bangladesh for apparel production. There the minimum wage for garment workers is $66 a month, the second-lowest in the world. Although safety standards are better than in Bangladesh, low pay, long hours, and employers breaking laws are common there, unions say.

In February 2012, Asia Floor Wage Alliance, a Cambodian labor group, held a two-day "People's Tribunal on for Minimum Living Wages and Decent Working Conditions for Garment Workers as a Fundamental Right." Garment workers testified on their experiences of poverty, short-term contracts, substandard housing conditions and an epidemic of workplace fainting.

H&M was invited to attend but did not.

"The tribunal reveals a chasm between the CSR [corporate social responsibility] speak of international garment companies and the real situation faced by Asian garment workers," said Anannya Bhattacharjee, coordinator of the International Asia Floor Wage Alliance.

Bhattacharjee said that the core issue was that garment workers need to be paid more.

"The wage issue is a cross border problem and needs to be addressed as such. International players must work together and use the Asia Floor Wage figure to combat poverty pay in the garment sector," she said.

A year later, some 200 Cambodian workers, who sewed underwear for Kingsland Garment Company, a sub-contractor to H&M and Walmart, camped outside their factory in Phnom Penh and held a two-day hunger strike when the company suddenly shut down and seized payment of their legally mandated unemployment wages.

"We decided to start sleeping outside of the factory to prevent management from taking the machinery out," Yorn Sok Leng, 30, told Labor Notes, an activist media organization.

Within days, the companies paid them $235,000 in wages owed, handing the organizers a rare victory.

Next Step: Minimum Industry Wage

New protests across Bangladesh are forcing yet more changes. Strikes effectively shut down most of the garment factories for much of last week - as workers rallied to demand better wages and working conditions.

Days ago Bangladesh officials finally gave in and announced that the minimum wage would be raised for the first time since 2010. Persson, the H&M CEO, also agreed to support an increase in the Bangladesh minimum wage.

These incremental changes are not enough, says Muhammad Yunus, founder of the micro-credit Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and Nobel Peace Prize winner, who argues that a global approach is needed.

"I propose that foreign buyers jointly fix a minimum international wage for the industry," he wrote in the Guardian recently. "This might be about 50 cents an hour, twice the level typically found in Bangladesh. This minimum wage would be an integral part of reforming the industry, which would help to prevent future tragedies. We have to make international companies understand that while the workers are physically in Bangladesh, they are contributing their labour to the businesses: they are stakeholders. Physical separation should not be grounds to ignore the wellbeing of this labour."

Yunus also suggested raising the final retail price of an item by 50 cents. "Would a consumer in a shopping mall feel upset if they were asked to pay $35.50 instead of $35? My answer is no, they won't even notice," he said.

(Incidentally most U.S. retail chains have not signed on to the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. Instead, following the Rana Plaza collapse, Walmart and other companies announced their own voluntary monitoring systems and safety programs, which some activists say was little more than a public relations campaign. "It's not surprising, and the timing is fishy," said Brian Finnegan, global worker rights coordinator at the AFL-CIO. "The whole point of what we're doing is to make it binding and enforceable.")

- 184 Labor