'Tis the Season for Shareholder Activism

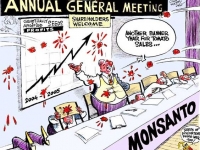

Every spring, thousands of annual general meetings take place across America. Many of these are banal affairs where CEOs use their big day to unveil their latest product, announce record profits, or otherwise make a media splash and get their votes of confidence from the stockholders who own the companies. You've seen it before: Bill Gates grins on stage as he touts Microsoft's New Feature. There's a colossal screen above Gates' head with a close up of his face, and the audience of thousands goes into thunderous applause every time he finishes a sentence.

Shareholder meetings are also the one opportunity each year where minority shareholders and advocacy groups have a chance to speak directly with the company boards in a public forum. Participation ranges from mild-mannered opposition to radical, attention-getting activism. In 1998, for instance, environmental activists from Amazon Watch splashed fake blood on the exterior of the Occidental oil company's headquarters and carried a "pipeline" of eight oil barrels welded together into the lobby of the building. Other meetings have prompted large scale banner drops, traffic obstructions, and puppet parades.

Amazon Watch's Leila Salazar, who was present at this year's ChevronTexaco meeting, believes that participating in these annual meetings is a useful way to be heard as an activist. "A lot of times we don't have that access." She says. "Its rare to be able to go and meet with companies that normally wouldn't listen to activists."

The meetings are also a convenient springboard for social responsibility investors and NGOs to introduce resolutions for shareholder votes to change company practice and generate media attention for their cause against standing policy at a company's expense.

That's exactly what a consortium of groups, including Rainforest Action Network (RAN) and the United Steelworkers Union, aimed to do in mid-April at the lumber giant Weyerhaeuser's annual meeting. They assembled a group of shareholders who collectively owned more than $400,000 in Weyerhaeuser stock to ask pointed questions to board members about the company's practices of recklessly logging endangered old-growth forests in North America, using wasteful tree-cutting procedures, and abuse of trust in the cutting of billions of dollars worth of cedar forests on the Haida Nation tribe's lands in British Columbia.

Weyerhaeuser CEO Steve Rogel's anticipated his Big Day might be ruined and brought in a large contingent of security guards and eliminated the custom of allowing shareholders to ask direct questions to the board members. Instead, shareholders were directed to write their questions on cards, which board members then chose from.

| Resolving to Change Below is a list of While the cosmetics company has removed products containing any ingredients on a list of chemicals known or suspected of causing cancer, genetic mutation, or birth defects from European products, it has not done so for its US products. The recent shareholder's resolution points to the chemicals still found in US products -- from petrolatum, to known carcinogens to reproductive toxins -- and asks for a worldwide ban. Ford Motor Company As the maker of a number of inefficient passenger vehicles, such as sport utility vehicles(SUVs) and pickups, one resolution points out that "Ford's average fleet fuel economy has been lower than any other major automaker since 2000." The shareholders requested that the company link a significant portion of senior executive compensation to progress in reducing lifetime product greenhouse gas emissions from the company's new passenger vehicles. Hasbro Hasbro makes most of its toys in overseas factores. A resolution to be presented at their upcoming meeting acknowledges the recent rise in awareness about human rights abuses and the denial of labor rights in overseas subsidiaries. Here, the shareholders went as far as to ask the company to promise to give all workers the right to form and join trade unions, to refuse to use bonded or prison labor and to refuse to use child labor. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company This resolution sites a recent World Bank study which predicts "a complete economic collapse will occur" unless there is a response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The study estimates that the HIV/AIDS crisis in Africa, where this company has operations in over 50 countries and employees more than 15,000 workers, will continue to grow. The resolution argues that HIV, along with malaria and TB, "can directly impact our company's bottom line through decreased productivity, increased absenteeism, ballooning healthcare and disability costs," and what they call "the destruction of human capital." It asks, therefore, that the company make an effort to evaluate and report on the effects of these diseases on their companies. ExxonMobil The company has had eight resolutions filed against it for its shareholder meeting One is led by the New York City Employees Retirement System, and it suggests that ExxonMobil rewrite its equal employment opportunity policy to include protection for workers regardless of sexual orientation.

|

From the company's perspective, the meeting did not go well. Many shareholders and representatives were furious that they were unable to communicate directly with the board. The Steelworkers said they submitted more than fifteen questions in the meeting and got just one response. Some of the attendees began shouting and were forcibly removed from the meeting. RAN's Old Growth Campaign director Brant Olson said that Weyerhaeuser's elimination of direct question/answer sessions in the meetings "set a dangerous precedent for other publicly-owned company meetings. It also shows the contempt Weyerhaeuser has for its shareholders - the people who actually own the company."

Steve Rogel told the press after the meeting, "Obviously there are elements of society who will do anything to have their views heard." Yet it was Weyerhaeuser's attempt to stifle the activists that really sent a message that day. News about the meeting spread throughout the local and national press. That day, The New York Times ran a story under the heading "Manager to Owners: Shut Up."

Weyerhaeuser's spokesman Frank Mendizabal's excuse to the Times was that Weyerhaeuser was trying to "ensure the meeting was orderly and that as many questions as possible were answered." Despite the tactics they were up against, RAN and the other groups see the day as a victory. Although they weren't allowed to speak directly to the board, Rogel has since backtracked and promised to hold two-way discussions in all future shareholder meetings.

More often than not, the controversy during shareholder meeting season revolves around the resolutions filed by investors.

It's very rare that a resolution relating to social or environmental issues in a shareholder meeting actually passes. In most cases, they are used to put pressure on company management and increase the level of debate. In some cases, resolution will be withdrawn by the filer before it is presented for a vote in a shareholder meeting.

In January 2004, for example, an environmental resolution for J.P. Morgan Chase's shareholder meeting was withdrawn when, after some negotiation, the company agreed to establish an office of environmental affairs reporting to senior executive staff that assesses environmental impact of the projects it financed. Steven Lipman of Trillium Asset Management, one of the negotiating entities with Morgan Chase, says the negotiations "centered on educating the financier that it was accountable for its investments."

"We were prompted to make a campaign out of Morgan Chase's environmental policy because it was working on immensely destructive projects like the Three Gorges Dam in China," Lipman adds

At this year's Whole Foods annual meeting in early April, a resolution to force the supermarket chain to label all of its genetically modified foods was voted on, and lost. But in that very same meeting, Whole Foods' CEO announced that it would, after all, label all of the products it sold that were genetically modified. But Whole Foods' policy switch didn't happen overnight - the social investment firm Trillium had been campaigning since 2001 to get Whole Foods to adopt the labeling, concentrating its arguments on how it was in Whole Foods' economic interests to adopt a GM labeling policy. A spokesperson for Whole Foods told CorpWatch that it was a "little premature" to publicize a response, and that the company was still in the "evaluation phase."

Getting a business to change its practices often takes at least a few years, with outside activist pressure and inside shareholder leverage forcing a company's hand. "Most policy changes that a company adopts are the product of campaigns a few years in the making," says Michael Passoff, who works in the Corporate Social Responsibility Program for the San Francisco-based As You Sow, a leading organization in the strategizing and organizing of shareholder campaigns. "In shareholder meetings, board members can be forced to hear questions that they otherwise wouldn't have had to."

All shareholder votes on resolutions relating to social and environmental responsibility causes are in fact non-binding. But the resolution process remains powerful, however, because it allows for strong questioning by shareholders and strong questioning can put company leadership on the spot.

"It's important to remember that the CEOs want to use their annual shareholder meetings to show off how well the company is doing," Passoff says. A company can cut a deal with the shareholders, see a resolution withdrawn before the meeting, and avoid the PR disasters like what happened to Weyerhaeuser. The good esteem of the shareholders - even minor ones - is a commodity in its own right.

The U.S. Security and Exchange Commission has set stringent rules in the resolution filing process for shareholder meetings. A resolution on an issue must receive a minimum of three percent of the vote in the first year for it to qualify for re-filing the following year, with the minimum tally rising to six percent and then to 10 percent in the second and third years. Once a resolution is backed by a full 10 percent of the shareholders, the company will either negotiate or activists will try a new resolution.

If a resolution fails to meet the minimum vote total - say, less than three percent in the first year - then the resolution and any other resolutions relating to the issue it concerns can not be filed for three years. For example, a failed resolution urging fairer hiring practices for women means that filings relating to all other equitable hiring practices are in effect banished for three years from the company's annual meetings. Therefore it's crucial that the resolutions be strategically composed. "One of the worst things that can happen in a movement to reform company practice is when inexperienced activists file a badly written, under-researched resolution," says Passoff.

Most important, is the link to increased profit. It may seem ironic then, that activists and communities that are often seen to value social justice over profit would be involved in framing these resolutions. In fact, if you read language of the actual resolutions, you might think the authors were interested only in the bottom line. In reality, it's quite the opposite. Many shareholder groups are participating in the process because they believe that such resolutions can change the world.

Until recently, most of the heavy lifting in shareholder activism was conducted by religious investors. These faith-based efforts have been spearheaded by the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR), a 25-yr-old organization that filed 264 shareholder resolutions in 2005. The ICCR has been a leader in religious investing for the past 30 years, and now consists of a coalition of 275 groups that represents an estimated $110 billion in capital.

This April for example, the ICCR-affiliated Adrian Dominican Sisters forced the pharmaceutical giant, Schering-Plough, to agree to list all of its federal and state political contributions, including those made to public policy groups or "Section 527" organizations. And Time Magazine just named Amy Domini, founder of Domini Social Investments, which manages $1.8 billion in assets, one of the 100 most influential people of 2005. Domini, who serves on the board of the Church Pension Fund of the Episcopal Church in America, has tackled the alcohol and tobacco industries as well as weapons contractors.

"We keep asking questions in the hope this will cause some soul-searching," Sister Susan Jordan, a Catholic nun and coordinator of the Midwest Coalition for Responsible Investment (one of the ICCR's member coalitions), told Reuters earlier this week.

"As Christians we talk about gospel responsibility...living more simply and not buying into consumerism, making the concerns of the poor your own, reverencing the environment and creation. All of those...have implications when you think about issues and companies," Jordan said.

Considering the recent political power that religion has played in the US, it may come as no surprise that companies are taking these groups seriously. Michael Passoff says that nuns are the most formidable figures among socially responsible investors. "You haven't seen shareholder activism until you see a nun battling it out with the CEOs. They can be devastating."

- 104 Globalization

- 116 Human Rights

- 183 Environment

- 184 Labor

- 185 Corruption

- 190 Natural Resources