Subsidizing Contractor Misconduct: Calvin's Story

Calvin Bryant is a true son of Savannah, Georgia.

Born in 1985 and raised just ten miles from the Imperial Sugar plant in Port Wentworth, Bryant went to Savannah High School and settled down to make a life for himself. He never had any ambition to go to college or see the world; his hometown was enough. "I never thought about leaving Savannah," he says.

The Imperial Sugar plant is another true son of this part of Georgia.

Since 1916, the plant (formerly owned by the Savannah Sugar Refining Corporation) has been processing sugar and providing jobs in Savannah. Among the plant's regular customers is the federal government, which has spent millions of federal dollars buying its sugar and related products.

Subsidizing Contractor Misconduct Full Report (PDF): Subsidizing Contractor Misconduct Part One: Tyson Foods - Rodney's Story Part Two: Imperial Sugar - Calvin's Story Part Three: Verizon - Alma's Story |

And about half that time, factory operators have been aware that airborne sugar can be highly flammable. A 1967 internal memo to company leadership went so far as to emphasize that a massive explosion could take place unless some basic housekeeping was regularly done at the refinery. And in 1998-one year after Imperial Sugar acquired the refinery-a worker was severely burned in a sugar-dust explosion at Imperial's Sugar Land, Texas refinery.

Bryant knew nothing of this when he was looking for work. He had bopped around a few odd jobs and was looking for something better when he caught a break at the plant. "A friend of mine worked there and he recommended the job to me. I heard that they paid more than a lot of [places and that people] can make decent money at the time," he says.

Bryant took a job as a "package attendant," operating a machine that organized the packaged sugar products as they came down the final stage of the assembly process, and occasionally clearing out jams on the line. He'd been on the job ten months when February 7, 2008, rolled around. He was 23 years old.

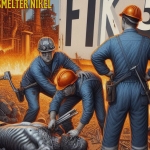

That was the day when the Imperial Sugar plant exploded. A spark first triggered a small explosion close to the factory floor. But it was the secondary explosions, from dust wafting in the air, that did the trick. A catastrophic series of detonations burst in the air, splashing flame throughout the facility. The resulting fires gutted the plant, killed 14 people, and injured another 36, mostly with burns. To this day, the event numbers among the worst industrial incidents in modern U.S. history.

Bryant was working his usual shift; he felt the blast before he heard it. "What I remember was that the building shook," he says. "And then the lights went out. And then there was like a force of air or something, and I went up into the air. And when I came back down on the floor, a big ball of fire was coming toward me. And after that, everything was on fire."

Racing the Flames

Bryant and a few of his co-workers raced for the exits ahead of the flames. But they were stuck on the third floor where the blast had caved in most of the usual exits.. "There was just too much fire." As they raced down a stairwell, they finally found a door they could use to get out.

By the time Bryant stumbled out of the plant, he had sustained second- and third-degree burns over forty percent of his body, and his days of ordinary pleasures, like playing basketball, were over. He spent three months in the hospital, but that was just the beginning of his new life. When he was finally released, he couldn't feed or bathe himself and needed nursing care every moment of his waking day.

Six years later, Bryant can feed himself, but only because he can fit special utensils onto his useless hands. "I can't grip or pick up certain things," he says. "Like, a glass of water. I can't pick it up with one hand."

Like many of the Imperial victims, Bryant sued and ultimately settled for an undisclosed amount. He hopes this money will keep him in food and clothes, because for the blue-collar, high-school graduate who had expected to work with his hands all his life, his injuries have left him without many options.

"I'm not able to work," he says. "Not at all. Now, I spend my days with friends and family, trying to stay busy."

After the explosion, the U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) investigated and found that not only had factory managers known about the fire threat from airborne sugar dust, they had witnessed numerous such fires break out at the plant in the years before 2008.

Indeed, factory managers used to routinely allow granulated sugar to accumulate until some workers reported that it was "knee-deep" in some areas. Company managers had also not bothered to install effective venting or dust-removal systems for critical conveyor belts where sugar dust might accumulate, or for the overhead spaces where the crucial secondary explosions were likely to take place.

In short, then-CSB Chairman John Bresland concluded, the Imperial Sugar fire was "entirely preventable." An Imperial Sugar representative did not respond to a request to comment for this report.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) investigated Imperial Sugar's Port Wentworth, Georgia and Gramercy, Louisiana facilities after the explosion and initially proposed a whopping $8.8 million fine against the company-the third largest in OSHA's history up to 2008. Imperial agreed to pay $6 million in penalties and implement abatement measures to resolve OSHA's allegations. But no felony charges were ever sought against anyone at the facility.

And despite this loss of life and the survivors' crippling injuries, in the years since the explosion the federal government has continued doing business with Imperial Sugar. It received about $30.7 million in contracts, mostly with the Department of Defense's agency that supplies the commissaries used by military personnel, retirees and their families. In 2012 alone, Imperial Sugar's new parent company, Louis Dreyfus Group, received nearly $95 million in federal contracts, according to an investigation by the Majority Committee Staff of the U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee.

Calvin Bryant has remained in Savannah, but he's never gone near the Imperial Sugar plant again. "I feel that I never got no explanation when I was hired that any of that stuff could get out of hand," he says. "I'll never feel that they were held accountable like they should be. I mean, they changed my life forever."

Looking back, Bryant sums up Imperial Sugar's actions in two sentences: "They did what they had to do. And what they didn't have to do, they didn't."

This article is an excerpt from a longer and fully footnoted report. That report - "Subsidizing Contractor Misconduct: Three Contractors Who Won Big Despite Egregious Labor Violations" - can be downloaded here.